Some of these Panoramas of Lost London disappeared due to progress, some because of war, and some are down to dubious planning decisions.

The book by Hampstead Garden Suburb author Philip Davies opens a window onto a vanished past with more than 300 black and white photographs of people, places and buildings dating from 1870 to 1945.

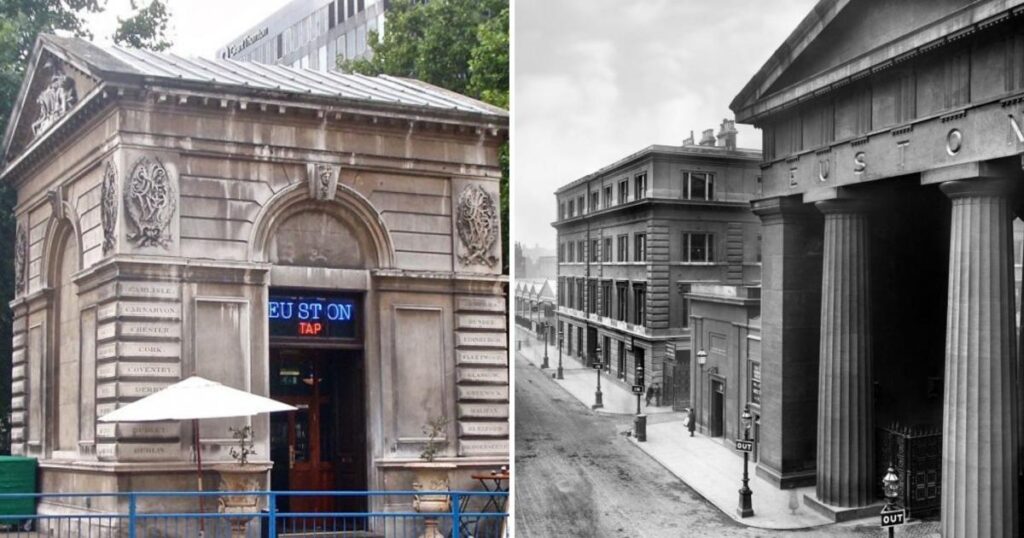

Among the most mourned monuments in London is The Euston arch, which was built in 1837 for the London and Birmingham Railway as the grand entrance to Euston Station.

It was designed in Roman style, 70 feet high with four Doric columns and bronze gates, with Euston on the architrave in gold lettering.

It was flanked by two lodges with bronze gates – one for carriages carrying passengers boarding trains for the North and Midlands, another for parcels and heavy goods.

Some criticised it as “gigantic and absurd” while others praised it as “noble,” but either way, the arch and station were scheduled for demolition in 1960 as part of British Transport Commission plans to electrify and upgrade Euston Station.

Both were Grade II-listed and there were questions asked in Parliament and a bid to protect it or even rebuild it elsewhere with MPs and figures such as poet laureate Sir John Betjeman and architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner voicing support, alongside The Victorian Society.

A group of architects even tried to delay demolition by climbing the scaffolding around the arch with a 50 ft long banner saying “save the arch”. But Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, who had the final say, refused to spare it.

The Architects Review decried its “wanton and unnecessary” demolition, blaming the British Transport Commission, the London County Council and the Government “who are jointly responsible for safeguarding London’s major architectural monuments, of which this is undoubtedly one”.

The Review added: “In spite of it being one of the outstanding architectural creations of the early nineteenth century and the most important – and visually satisfying – monument to the railway age which Britain pioneered, the united efforts of many organisations and individuals failed to save it in the face of official apathy and philistinism.”

Historian Dan Cruickshank, who writes a foreword to the book, has recovered part of the arch, which was dumped in an East London canal to fill a hole.

Some of the stones are on display behind the bar of The Doric Arch pub which takes its name from the vanished landmark. And the only remaining part of it – one of the flanking lodges – has been turned into a pub, The Euston Tap.

The row over the demolition undoubtedly helped Sir John Betjeman when nearby St Pancras Station was threatened with a similar fate in the mid 1960s.

The restoration of the spectacular engine shed and Gothic railway station behind the facade of the The Midland Grand Hotel is considered one of London’s architectural jewels, and Sir John has a statue in the station by way of a thank-you.

Dan Cruickshank said: “Few photographs are more powerfully evocative than those of lost buildings of great cities. The photographs in Panoramas of Lost London have astonishing emotional power and appeal.

“Even if the actual buildings cannot be brought back to life, this evocative and haunting book is the next best thing. Like its many photographs, it is pervaded by an intangible magic.”

Panoramas of Lost London: Work, Wealth, Poverty and Change 1870-1945 by Philip Davies is out now by Atlantic Publishing.