The writer, an FT contributing editor, is chief executive of the Royal Society of Arts and former chief economist at the Bank of England

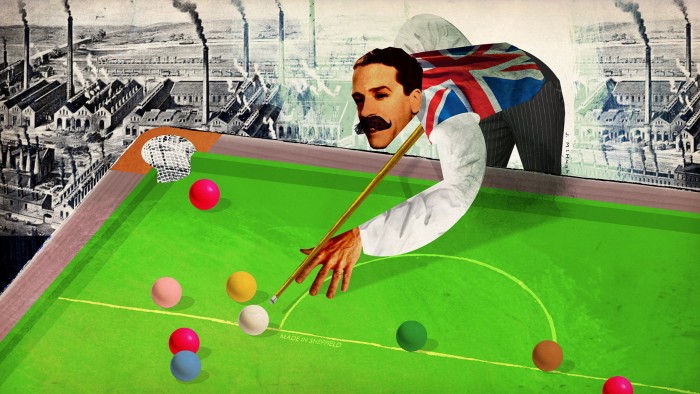

The World Snooker Championship concluded this week at the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield, its home for the past 48 years. This year’s was the biggest ever, attracting nearly 200mn viewers globally to see the first Chinese world champion, Zhao Xintong. At the start of this century, the equivalent viewing figures were less than 5mn.

Despite its success, next year could well be the last for the Crucible as host as its existing agreement with the World Snooker Tour comes to an end. The WST wants a larger, more state-of-the-sport venue, perhaps with Saudi Arabia or China as hosts and backers. The commercial case is clear.

The global market for snooker is growing rapidly, led by a grassroots explosion in China and the Middle East, filling large sports stadiums and with rising prize money. Capacity at the Crucible, at under 1,000, is small and unchanged in half a century. Prize money for the world champion, at £500,000, is modest by modern sport standards.

The magnetic attraction of money has already led several sports to move to where the pockets (financial, not snooker) are deepest. The centre of gravity in cricket has switched to India, with the Indian Premier League the largest global cricketing franchise. Saudi Arabia is now the global hub for boxing. A Saudi-backed alternative world golf tour began three years ago.

This external migration is not confined to sport. ARM (semiconductors), DeepMind (AI) and Darktrace (cyber security) were all world-leading UK companies snapped up by international bidders and, given subsequent growth, prematurely. Sold in haste, the UK is now repenting at leisure as it seeks to nurture the superstar businesses essential to shape industrial strategy and kick-start growth.

This is nuts. The UK can ill-afford to lose winners like these. UK sport, with its history and incumbency advantages, is a sector rich in success stories. Football, invented here in the 19th century, is now the world’s largest sport by popularity, participation and on some metrics revenues. Despite the country representing less than 1 per cent of the global population, the English Premier League is the leading football league by revenue anywhere.

Modern tennis, another 19th-century English invention, ranks among the top 10 global sports, with decades-long revenue and popularity growth expected to continue. The premier tennis tournament in the world is Wimbledon, with revenue of £400mn last year.

It was British Army officers that devised snooker during the same era. Smaller than football or tennis, the growth rates in revenues and participation are equally strong as it penetrates large expanding markets in China, the Middle East and prospectively India, where it was first played. Letting snooker slip from Sheffield’s grip at this point would be as myopic an act as selling an ARM, a leg or a Deepmind.

The government will only achieve national growth by growing the UK’s regions and nations. In pursuit of that, leaders in municipal areas and mayoralties have been handed more powers but not more money. Oddly, Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ growth speech in January offered precious little either to the regions or to sport. (The announcement of a new football stadium for Manchester United doesn’t count — the supporters mostly live in London.)

Yet, backed at scale, sport is one of the most effective drivers of local growth. There is no better example than Stratford in east London, home of the 2012 London Olympics. Its transformation from dereliction to gentrification came courtesy of £9.3bn in public money and, from the start, a focus on legacy. The All England Club which hosts Wimbledon has invested over half a billion pounds upgrading and extending its estate and government support for grassroots tennis runs to tens of millions.

The comparison with Sheffield and snooker is salutary. A fan of both, I am fully invested. Government, alas, is not. Investment per capita in the city of Sheffield is less than half Manchester’s and one-tenth the London borough of Westminster’s. Investment in Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre has been small change.

As a sport, snooker has never received a penny of public money. If we are serious about growth outside the South East, the playing field needs levelling. The chancellor’s Spending Review in June is an opportunity to do so. Investing in snooker in Sheffield would anchor it as the global hub, crowding-in the private finance that generates wider growth benefits as enjoyed by Stratford and Wimbledon. And an investment in snooker’s grassroots would create the talent pipeline necessary for sustaining success. China has 300,000 snooker clubs, the UK just a few hundred. Yet the Chinese world champion, Zhao Xintong, trains in Sheffield.

Wimbledon and Sheffield “fortnights” could become the north and south poles of sport in England. Catching, rather than selling, a rising sports star could drive growth and pride locally while boosting the UK’s standing globally. In this century, Sheffield and snooker could become as synonymous, and internationally recognised, as were Sheffield and steel in the previous one.

Industrial strategy is not about picking winners but sticking with them. For the UK economy, sport, snooker and Sheffield are a winning team and rising star. An investment here would deliver the holy grail of local growth to meet national objectives with global ambition. In the words of England’s finest 20th-century philosophers, Chas and Dave, it would be “snooker loopy” not to.