Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Anyone who was reasonably paying attention in their English classes at school would have come across the concept of pathetic fallacy — where nature seems to reflect the mood of the author or the main protagonist. Depression comes “sudden from heaven like a weeping cloud”, Keats warns us in his cheerful Ode on Melancholy.

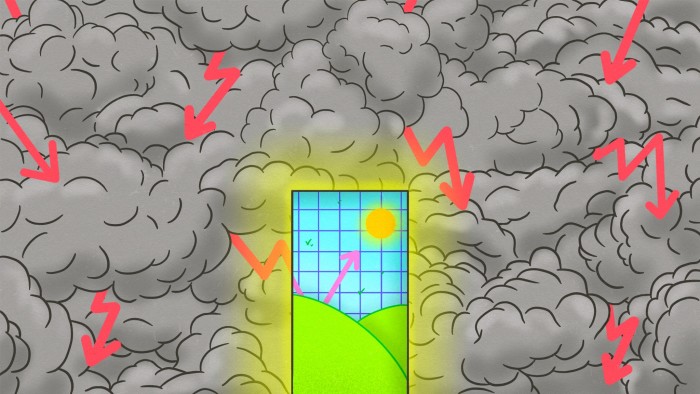

The feeling might go beyond literature. It’s been cold and damp outside, which seems to capture the mood of the UK when we look at the state of the economy. Much of Britain seems to be suffering from the winter blues.

Since the Labour Budget at the end of October, shares of domestically focused UK companies have underperformed more international peers. Pull up the share price chart of UK housebuilders such as Bellway and Persimmon (down 19 and 21 per cent respectively) or a building materials company such as Marshalls (down 25 per cent) and compare it with the FTSE 100, which is dominated by international earners (up nearly 7 per cent), and you will see what I mean.

This underperformance is logical — the Budget introduced additional costs on domestic employers in the form of higher national insurance and the rise in the National Living Wage, meaning these businesses had an implicit earnings hit. You see it particularly in people-heavy sectors such as retail and hospitality. Marks and Spencer estimates the national insurance cost alone will be £60mn (and roughly double that once the national living wage is added in); restaurant and pub chain Mitchells & Butlers puts the total bill at £100mn.

This has had a material impact on interest rate expectations. Higher employment costs must feed into higher prices for consumers, meaning that — so the logic goes — inflation will prove more stubborn. The Bank of England has just pushed back expectations of inflation hitting the target 2 per cent by six months — to the end of 2027. That means it could struggle to cut interest rates in any meaningful way. “Higher for longer” is now the standard view.

Simultaneously, the UK economy appears to be “flatlining” at best — the Bank has halved its growth forecasts. Put those two things together and the consensus forecast for the UK economy is “stagflation” — an unpleasant combination of high inflation and stagnant or declining growth.

But what if everyone is being too miserable? What if the consensus is wrong? Might this not present some interesting opportunities to the contrarian optimist who has mislaid their Keats and is ready to venture out without an umbrella, rain mac and wellies?

The market has focused on the inflationary impacts of the Budget. However, there are also disinflationary aspects too — particularly the incentive for employers to hire fewer staff and curtail wage growth where possible.

Last year, UK wages grew by about 5.3 per cent on average (2.5 per cent in real terms). But the labour market appears to be weakening, with vacancies and hiring intentions falling. Pay rise expectations for this year are nearer 3.7 per cent.

It is service sector inflation that has proven stubbornly persistent. Weakness in the labour market that reduces the bargaining power of employees is clearly not an encouraging outcome for the broader economy or those affected. But it might be what is needed to bring down UK inflation.

In my view, the more likely outcome for the economy is not stagflation but stagnation. This may sound equally grim. It is not. There is a policy lever that can be pulled in this scenario — interest rate cuts.

History shows that markets are poor at forecasting rate cuts. In the four previous rate-cutting cycles — 1990, 1998, 2001 and 2008 — rates fell far more than was being priced in by markets at the time. It would be no surprise if they did so again. The market expects three more cuts in 2025, taking the base rate to 3.75 per cent.

If I am right and the slack labour market leads to faster interest rate cuts than currently anticipated, where might you look for opportunities?

Housebuilding last year was still well below pre-Covid levels. If completion numbers recover and come anywhere close to analyst forecasts building materials producers in particular may merit consideration. These are currently suffering from a lack of volume going through their (relatively fixed) cost bases. Were interest rates to fall faster than expected, potentially stimulating housing demand, production could be stepped up with relatively little extra cost. The drop-through from a pound of extra sales to earnings would likely be substantial. A beneficiary might be brickmaker Ibstock, whose share price has fallen more than 15 per cent since the Budget.

Commercial property may sound a brave suggestion in a working-from-home world, but higher government bond yields have driven share prices often down to sharply below tangible asset value. Going into the Budget, British Land, for instance, had a net asset value (NAV) of about £5.67 a share. In the wake of the Budget its shares have fallen 7 per cent to £3.70 a share. Land Securities trades on a similar discount. Yet rental growth in a lot of areas is actually encouraging.

It is interesting that Assura, which owns healthcare property, such as GP surgeries, has just rejected bids from private equity business KKR at close to NAV suggesting others are seeing value in this sector now.

These are not share tips, they are merely seeking to highlight the extremities reached in some areas of the UK market. Often these shares come with attractive dividend yields. British Land pays more than 6 per cent; Land Securities nearly 7 per cent. These yields will look more attractive still if rates fall faster than expected. It suggests that investors brave enough to go against the crowd are being paid for their patience.

Where might I be wrong? Serious escalation of the global trade war would not help. And stagflationary periods in the past have often coincided with energy price shocks. Both are possible.

This is why within an overall portfolio investors need to hold a range of companies that can thrive in different backdrops. In other words, always carry an umbrella — even if you think the rain will hold off.

One of my favourite sayings is “The secret to happiness is low expectations.” The most interesting opportunities can often be found where expectations are lowest. If the assumed scenario for the UK is now stagflation, even stagnation could bring happiness to those whose portfolios are positioned appropriately.

You may find yourself wandering lonely as a cloud if you buy winter, post-Budget blues stocks now. But the temperature may only have to lift modestly against the forecast for that to change quickly.

Laura Foll is co-manager of the Lowland Investment Company and Law Debenture, which owns Land Securities, Bellway, Marshalls, Marks and Spencer, Ibstock