Ministers are facing growing calls for a national inquiry into the actions of rape gangs in towns across the UK, after Elon Musk reopened the decades-old scandal.

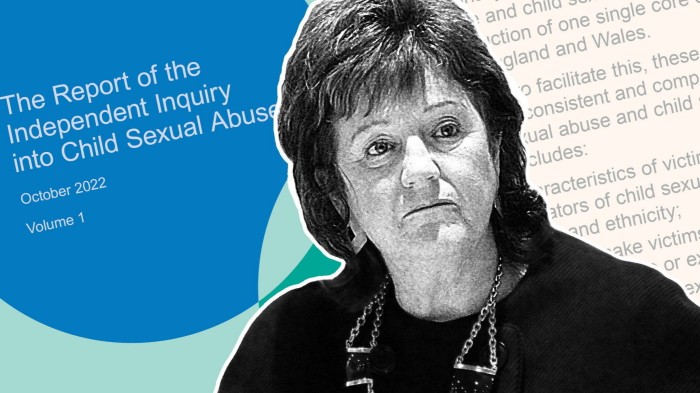

Yet an authoritative 2022 study set a blueprint for how to tackle the issue.

“We’ve had enough of inquiries, consultations and discussions,” the report’s author Professor Alexis Jay said on Tuesday. “We have set out what action is required and people should just get on with it.”

What should be done?

Jay’s report into child sexual abuse made 20 detailed recommendations, with a call for the Conservative government of the day to publish what steps it had taken within six months.

These included the introduction of a statutory requirement for individuals in some professions to report allegations of child sexual abuse to relevant authorities.

The inquiry also called for a national redress scheme to be set up to provide compensation to victims, and the creation of a Child Protection Authority with powers to inspect any institution associated with children.

Many of the recommended changes have not happened, either because they were not implemented or because last year’s general election halted laws that were passing through Parliament.

What has happened already?

A key recommendation was for more robust age verification on online sites, as well as a mandatory online pre-screening for sexual images of children.

While the previous government brought in the Online Safety Bill 2023, which expected social media platforms to enforce age limits and age checking, it did not include pre-screening for sexual images of children and young people. The law became the Online Safety Act, which comes fully into force this year.

The main recommendation of the Jay review was for people who work with children to face criminal sanctions if they fail to report sexual abuse claims. On Monday, home secretary Yvette Cooper promised this would feature in the upcoming Crime and Policing Bill.

She also said the government would legislate to make grooming an aggravating factor in the sentencing of child sexual offences.

Downing Street insisted plans were already under way to bring these changes into law before the issue was raised by Musk last week.

“We are working at pace to go through all the recommendations,” it said. “These recommendations were made in 2022 and weren’t acted on by the last government, this government has already started to act on the recommendations.”

What has not happened?

However, many of the recommendations have yet to be brought in. These include ending the three-year cap for child sexual abuse victims to make a personal injury claim; a national financial redress scheme for victims; and changes to the Criminal Injuries Compensation Scheme.

After the Jay review came out, the previous Conservative government promised to consult on the measures, but never brought them into law.

The report also called for therapeutic support for victims, something that was not implemented.

Extending schemes that bar certain people from working with children, and extending these overseas, have also not been enacted.

Appointing a dedicated cabinet minister for children was also recommended, though both the Tory and current Labour government said the responsibility already lies with the education secretary.

What happens next?

On Wednesday the opposition Conservative party will seek to ramp up pressure on the government by trying to force a vote in the House of Commons on holding a new inquiry into the grooming gangs scandal.

The Tories have put forward a “reasoned amendment” to the Children Wellbeing and Schools Bill calling for a full national inquiry.

They argued that Jay’s report only examined six specific towns — when grooming gangs had operated in more than 40 towns in the past — and accused the government of “blocking a full national inquiry”.

But victims minister Alex Davies-Jones said Jay had already carried out a thorough report with testimony from more than 700 victims.

She added: “If, once those [Jay] recommendations have been implemented, there is further work to do, then of course we will do that work.”

What about prosecutions and convictions?

In 2014, the UK launched Operation Stovewood, described as “the single largest law enforcement investigation into non-familial child sexual exploitation and abuse in the UK”.

Some 39 people have been convicted, according to the National Crime Agency, and jailed for a combined total of almost 500 years.

Ten trials have been listed for this year and 2026, and there were more than 40 ongoing investigations, according to the NCA. More than 220 people have been arrested or attended a police station voluntarily.

Two brothers are due to be sentenced in Sheffield next week after they were convicted last month of raping girls 18 years ago, plying young victims with drugs and alcohol before luring them to locations where they attacked them.

In October, three brothers were found guilty of child sex offences in Barrow and Leeds between 1996 and 2010. Girls abused by two of the brothers were as young as six or seven when the abuse began, and it lasted several years, according to the Crown Prosecution Service.

Convictions last year also include that of a former limousine driver who the CPS said had “systematically groomed and abused” young girls in the Rotherham area between 2005 and 2015. The man was given a 24-year prison sentence after he was found guilty of several sexual offences against eight girls, who were aged between 12 to 17 at the time.