Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A common pastime of the very rich is musing on where they’ll go to escape higher taxes. In the old days, my response was furious and full of English inverse snobbery: “How many yachts do you need?” I’ve stopped doing that, since it turned out they meant it.

Some have gone; others are going. It would be a mistake to keep betting that it’s just a trickle: the flow is getting stronger. Just when we most need their energy and enterprise, we are pushing it away: and making it harder to lure fresh talent.

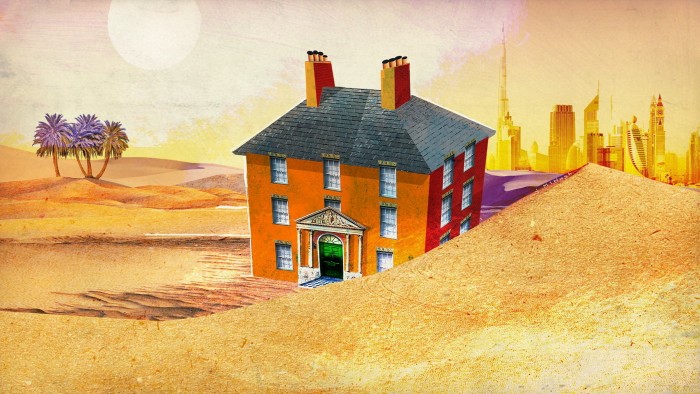

There’ll be no violins playing for people who uproot their kids to the new Abu Dhabi branch of Harrow school, or sun themselves in Milan. But there is already huge anxiety among charities and arts organisations about the loss of donors. Like it or not, the rich have an outsize impact on investment, the tax take and philanthropy. Other countries want and value them. Why don’t we?

The increasingly footloose nature of capital, and the impossibility of knowing how much of it might move, is what stayed the hand of multiple chancellors — including Labour’s Gordon Brown — from ending Britain’s antiquated non-dom regime. The former Conservative chancellor Jeremy Hunt admits that he was “very nervous” about his decision, in March 2024, to phase it out. Rachel Reeves’ doubling down on that decision, by going after inheritance tax, seems to have been the last straw. Her recent attempt to soften the policy didn’t go far enough.

The rich are used to paying tax: 74,000 non-doms paid the UK government £8.9bn in taxes in 2022-23. But hit someone’s life’s work, and their children, and it’s personal. By changing the inheritance tax regime, and capping business and agricultural property relief, the Budget has left a lot of people — some expats and some not — reassessing their lives and whether the UK values them. The knock-on effects could be much bigger than the Treasury assumes.

The structural challenges predate Labour. Brexit has been a slow puncture, turning Britain from a net importer of millionaires into a net exporter. Between 2023 and 2024 the numbers leaving more than doubled, according to investment migration advisers Henley & Partners — meaning the UK lost more wealthy residents than anywhere except China. There are many possible reasons: nervousness about Britain’s deficit and sluggish growth, fears of further tax rises, failing public services. But the assault on inheritance comes up in every conversation.

“If my wife and I died tomorrow,” one successful entrepreneur tells me, “our kids would face paying 40 per cent out of taxed income. My business would have to close.” In Dubai, this man got a golden visa and residency permit a mere 24 hours after taking a blood test and filling out a form. Does he really want to live in a desert, however fancy? No. But he can start a business from anywhere — and he hasn’t worked his socks off for decades to lose his legacy.

It shouldn’t be like this. At a time of political turmoil elsewhere, the UK can offer stability. The Labour government has at least four more years in power, with a solid majority. We should not be accidentally losing people who wanted to stay. The Australian Financial Review quotes one Australian executive as saying that the April 6 deadline to avoid Australian assets being caught in the inheritance tax net has “crystallised the decision to leave”.

Donald Trump’s assault on science in the US presents an opportunity to lure talent. France’s universities are putting out the welcome mat; so are Britain’s. But some of those involved say that our tax regime and visa restrictions are proving a turn-off to the kind of young PhDs and entrepreneurs who might help to build the next DeepMind. Discussions are running up against the fact that while it can take 10 to 15 years to build a successful start-up, the new tax regime means no one wants to stay for more than a handful. Tax lawyers warn the UK could become a land of four-year postings.

When people start saying that the smart thing to do is to get out of Britain, we are approaching a tipping point. “I’ve lived in London for 37 years,” says David Giampaolo, founder of the investor club PI Capital. “I’ve lived through war, Brexit, and the financial crisis. Nothing moved the needle. But now I see friends, investors, philanthropists, leaving. We’ve hit an inflection point. It doesn’t matter who wins the next election, if this government doesn’t get a grip on growth.”

The gathering gloom coincides with fierce competition for migration investment. Property prices have soared in Milan, since Italy started its “empty London” preferential tax package. This comes after years of a slow brain drain of middle-class talent: junior doctors seeking better lives in Australia; school leavers going to US universities; doctoral science students grabbing opportunities in Singapore.

The new government has a load on its plate. But it has adapted fast to the changes in the transatlantic alliance. It should be similarly nimble about rethinking inheritance. Analysis by the National Farmers’ Union has suggested that the Treasury and the OBR wildly underestimated the impact of the capping of business and agricultural property relief: that 75 per cent of commercial farms will be hit by the changes to APR and BPR, not the 27 per cent the government originally claimed.

If they’ve made a similar miscalculation about non-doms, the resulting brain drain will be very hard to reverse. The chancellor is approaching her Spring Statement amid a sea of troubles. If I were her, I’d be doing everything in my power to change the growing sense that the smart money isn’t on Britain.