Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In his Principles of Political Economy, published in 1848, John Stuart Mill wrote that, before industrialisation, jobs were “almost equivalent to an hereditary distinction of caste”, with “each employment being chiefly recruited from the children of those already employed in it”.

But Mill was wrong. As Patrick Wallis, professor of economic history at the London School of Economics, shows in this authoritative new book, non-agricultural work in England was “anything but hereditary between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries”.

“This was an economy and society in flux,” Wallis writes. “Cities and towns were expanding. Industry and services were growing. New types of work were appearing. For this to occur, sons — and daughters — could not simply take on the family trade.” It was apprenticeships that enabled changing demand in the economy to be met with an appropriate supply of labour. (If this discussion sounds topical it is perhaps a sign that some labour market issues never really go away.)

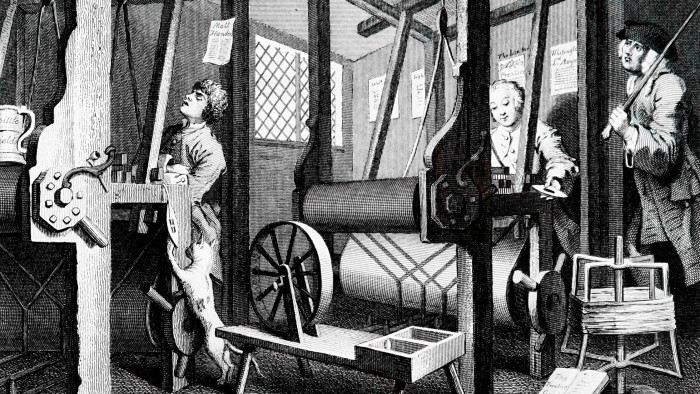

Wallis can write with confidence because he and his colleagues have had access to a new “digital treasure-house” of data — apprenticeship records taken from guild, urban and national sources. He takes us back to a world of tallow chandlers, girdlers, glovers and barber surgeons.

Apprenticeships were almost an unintended success. The Elizabethan law introduced in 1563, the “Statute of Artificers”, made a seven-year formal apprenticeship a requirement in many trades outside farming. The law was designed to limit the flow of workers from agriculture into other commercial activities and thereby keep agricultural wages down.

And yet, Wallis writes, “Early Elizabethan London was, in truth, a city built on apprentices.” The requirement for apprentices to complete seven years of training remained in place until 1814 but apprentices often did not complete seven years with one master, having the option to move on early or switch to a different trade. Moreover, the early modern system was “a contract to purchase training, not an agreement for employment”. Apprentices rarely stayed on as a permanent employee, but rather left to ply their own trade. This flexibility was a great strength.

Contrary to Adam Smith’s view, set out in The Wealth of Nations (1776), that apprenticeships restrained competition between businesses, Wallis suggests that they became “an ingredient in industrialisation, not a brake on it”, initiating “an extraordinary period of structural change”.

They did not promote social mobility, however. “Masters took those who had funds as well as ability rather than selecting apprentices by merit alone,” Wallis writes. Parents played a vital role too; he compares the energy that early modern parents invested in “identifying a good master for their son or daughter” to today’s families’ fretting about schools or universities. In the mid-18th century, parents were advised by one author to find a master based on his “Good-Nature, Sagacity, and Knowledge of his Business”.

These lessons from history can help us think about training today. While most seem to be in favour of apprenticeships, in practice (in the UK at least) the results can be mixed. Reconnecting with the original principles could be useful. As Wallis points out, it is the acquisition of tacit knowledge, as much as skills, that counts. Good apprentices pay attention and learn, “stealing with their eyes”, as another scholar has put it.

“At every point in the three centuries from 1500 to 1800, apprenticeship was the main focus of human capital investment in England,” Wallis states. Instead of seeing it as an exploitative system, he offers a more positive interpretation: “Most apprentices might instead find themselves places . . . that offered them the chance to learn trades from masters who had proven their abilities and would not treat them as low-cost labour.”

This thoroughly researched and well-argued book reminds us, if it had slipped our minds, that the development of future human capabilities remains vital, no matter what wonders the tech bros continue to promise us.

The Market for Skill: Apprenticeship & Economic Growth in Early Modern England by Patrick Wallis Princeton University Press £38, 480 pages

Stefan Stern is the author of ‘Fair or Foul — the Lady Macbeth Guide to Ambition’ (Unbound)

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X