Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

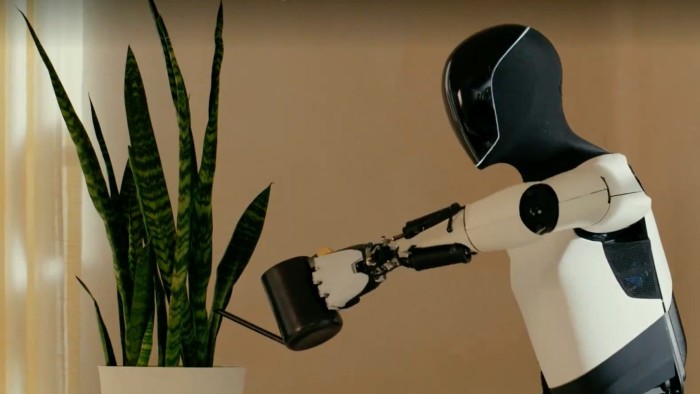

Elon Musk, facing disarray in his corporate and government ambitions, remains gung-ho on the rise of robots. The tech billionaire, Tesla boss and government efficiency tsar this week reiterated his aims of having 1mn Optimus humanoids by 2030, or even 2029.

Swiss industrial giant ABB, which plans to spin off its robotics arm next year, will be hoping others share his view. The group in 2022 became the first manufacturer to sell 100,000 robots, but the division’s $278mn of operating profit before amortisation represents just a snip of the company’s $6bn total.

Their long-term prospects notwithstanding, robotics illustrate another tariff own goal. Two problems: depressed buyers and unhelpfully global supply chains. ABB, like Japan’s Fanuc and Kuka, a German manufacturer acquired by China’s Midea in 2016, is focused on industrial applications, building collaborative robots that can work safely alongside humans.

Uncertainty unleashed by Washington’s tariff policy engenders paralysis on the shop floor. Carmakers, once a key source of new demand for robotics, have been at the centre of the tariff storm. Few will opt to expand or upgrade factory kit when sales expectations are clouded at best, dented at worst. Other industries may not fare much better.

The US boasts a clutch of robotics makers, such as Apptronik and Figure AI. But China is a key supplier of materials and components used in actuators — the machines that turn electrical impulses into physical motions — such as precision bearings. Actuators make up more than half of total materials’ costs, according to Bank of America calculations. Even Musk flagged issues securing permanent magnets from China for Tesla’s Optimus robots.

Higher costs or, worse, inability to secure supplies could flick the reverse switch on US robotics ambitions. While China leads the duo on making industrial robotics, it shares the top slot with the US when it comes to humanoids, which deploy dexterous joints and artificial intelligence to move and act more like humans.

Besides, even humanoids may be losing some of their shine. Shenzhen-based UBTech is a leader in this field, boasting more than 900 corporate clients in 50 countries when it listed in 2023. This month, it tempered its forecasts for shipping 500-1,000 industrial humanoid robots back to 500. That in turn prompted Citigroup analysts to downgrade this year’s revenue forecasts by 17 per cent — and augers poorly for the lofty expectations of Musk and others who expect armies of humanoids to fill factories, hospitals and, ultimately, homes.

China remains by a long stretch the biggest market for robots: just over half the world’s robots are installed there. It is also number two when it comes to manufacturing, well behind Japan but producing four times as many as third-ranked Germany. The US market languishes far behind.

Tariffs threaten to delay the adoption of this futuristic technology. On the plus side, because robots will be slower to arrive, this is one instance where trade levies really may result in more American jobs.