To arm ourselves against Reform’s rise to power, we need first to recognise the most vulnerable parts of our current political landscape.

The flickering candle of democracy burned brighter recently. Anti-Trump politicians won general elections in Canada, Australia and Romania, and Trump’s own support has wobbled. The consternation expressed by MAGA Senator Rand Paul and Joe Rogan about the deportations may be cutting through and unsettling parts of the MAGA herd. Even a slug can see that Trump’s “dangerous criminal aliens” tag is a stretch for 2-year-old deportees undergoing US cancer treatment.

Clown car or despot?

Yet we find ourselves in a curious state of suspension right now, unable to judge whether either Trump or Farage will be rumbled as clown car drivers or grow in strength and increase their grip.

Being undecided creates excuses for non-action. Since complacency is dangerous, it’s probably wise for democracy defenders to explore some challenges surrounding Reform’s rise.

Trump wannabies

In the emotive, far-right battle against ‘the ‘disease of wokeness’ among modern democracies, Trump is a massive inspiration to far-right wannabies who crave the same despotic power. If Reform UK wins the next general election, there’s a very real possibility that the cruel madness of Trumpworld could take root here.

The UK as we know it could change dramatically. Reform’s anti-DEI stance is a warning that diverse groups (Muslims, trans people, climate activists, left-leaning intellectuals, creatives, disabled people, journalists, scientists, women, and others) could be at risk, finding themselves, like their US counterparts, catapulted into a culturally hostile environment with restricted rights and work opportunities. We could also see UK versions of the ICE purges, denial of due process, constraints on intellectual and reproductive freedoms, and constitutional violations.

The shifts may be slow and subtle, or like the US, fast and overt. Either way, it’s serious and not just ‘somewhere else’ but potentially coming here too. Farage’s long-standing affinity with Trump’s politics couldn’t be a clearer flashing red light. Here are six forewarnings to consider.

1. Stranger danger

Within an eye blink of winning in 2024, Labour fell at speed from grace, damned by FreebieGate, winter fuel cuts, and a raft of other nasties. With its shallow majority, Labour can ill afford its reputational collapse. Reform is licking its lips in the wings, with current polling projecting a 40-seat majority.

Starmer’s hostile immigration rhetoric shows him still doggedly veering right despite the maths screaming the need to tack the other way for Labour’s own survival.

Starmer’s Blue Labour advisors are anti-pluralist, anti-woke and hold both the Labour Left and “radical progressive elites” in contempt. Starmer’s own Reform-lite madness is, arguably, either because he’s been mis-advised that it’s strategically effective, or because he’s too ideologically weak to resist, or because, as a politically unconfident traditionalist, he’s been radicalised. (For other radicalised shapeshifters, consider Matthew Goodwin, Robert Jenrick and Liz Truss.) Whatever the reason, Starmer’s Reform-lite stance is clearly further harming Labour’s support.

2. It couldn’t happen here

Despite Labour’s self-imposed frailties, it’s assumed that the UK isn’t vulnerable to the democratic collapse in the US because we have stronger mechanisms for removing would-be despots.

When Boris Johnson, following the Trump playbook, pushed the boundaries of lawfulness by trying to prorogue parliament, our constitution stopped him with a unanimous Supreme Court ruling. But the UK constitution lacks codified (written) protections and independent formal arbiters. As with the US, ultimately our democracy relies on the adherence of “good chaps” to conventions, and is vulnerable to bad actors ignoring them.

Johnson’s final demise was triggered by a whistleblower who exposed the Partygate scandal, precipitating a downfall from which he couldn’t recover. Without this serendipity, Johnson may have remained and continued modifying the rule book to fortify his personal power.

Johnson’s actions were smaller scale but of the same ilk as Trump’s. In Johnson’s place we now have the looming threat of Farage, a man fully embedded in the global network of grassroots, media and press far-right disinformation. It’s hard to know if Farage has an ‘inner despot’, but given his contempt for ‘progressive liberal values’ and democracy itself, he may be tempted to achieve his goals using Trumpesque anarchism. His desire to leave the ECHR raises the question of what other courts he’d reject. And as Trump demonstrates, incompetence isn’t necessarily an obstacle.

3. Trump action

Labour may be relying on voter dislike of Trump, reasoning that Farage’s affinity with Trumpism will deter voters in 2029. The theory is that our binary voting system will instead force them to hold their noses and opt for Labour, thus freeing the party to roll out unpopular policies in the meantime.

This is a dangerous gamble. Reform’s strong performance at the local elections tells against the notion that voters are deterred by Farage’s fondness for despots.

It also ignores the contextualized negative power of first impressions. As voters are now fully disillusioned with establishment politics, they are far less likely to forgive Labour its initial missteps. Also, Labour is failing respectfully to acknowledge that there’s a limit to how often voters will tolerate being taken for granted.

Even if the UK electorate does hate Trump, although the Reform threat is now clear, voter contempt for Labour looks even stronger. The anger is particularly febrile because voters expected nastiness from the ‘nasty party’ but feel truly betrayed when confronted by the same callousness from the party that’s supposed to care. And Big Tech plans to harness this rage with a persuasive new post-truth reality between now and 2029.

4. Clickbait and cash cows

Certainly, Reform represents an alternative for voters deeply frustrated with the failures of establishment politics. But central to Reform’s success in the local elections was that the mainstream media (MSM) can’t stop talking about them. The party’s support is fed by indecent levels of MSM sycophancy that feeds our eternal fascination with the ‘maverick’.

The MSM have relentlessly generated ‘Reform curiosity’ by presenting the party as alternative, unfettered, liberating, gutsy and anti-establishment. In our quick-fix world, the party has acquired the allure of a naughty experiment. Like forbidden chocolate, its dark fascination has huge ‘engagement potential’ for the UK’s large ‘I’m so fed up I’ll try anything’ cohort. The MSM spent so long dangling the novelty clickbait that ‘Reform might surprise us’ that eventually it did.

So, we shouldn’t bank on Reform’s weaknesses being properly scrutinized. The MSM might dabble politely, but they aren’t going to change tack radically just because Reform now has some real local work to do. Pumping up Reform as a ‘refreshingly different, poke in the eye non-establishment party’, is such heady copium, the MSM won’t relinquish this carefully curated cash cow easily.

5. Thought shapers

A further danger is the assumption that parties follow voter preferences. Focus groups tend to regard party policy choices as reflecting the electorate’s support for principles like the NHS. But far-right parties don’t reflect voter thinking. Instead, they shape it to their own ends, driving the UK further right by any means available to them.

Kemi Badenoch will probably soon be replaced by Robert Jenrick, an extreme right Trump supporter whose willingness to co-ordinate with Reform could strengthen both. We shouldn’t take comfort from the idea that any allegiances with Reform would alienate voters because Jenrick doesn’t care. The far right is a prescriptive movement that uses social and press media to create a cultural environment in which anti-woke values become dominant. They aren’t responsive or beholden to the UK’s current progressive majority -their aim is to stamp it out.

6. Trojan Horses

To help achieve this end, far-right parties use camouflage and, again, here lurks danger. ‘Talking centrism’ is a means to obtain power. Once in power the pretence is abandoned. Farage plays down his rapport with the US’s “inspirational” leader when necessary, and has discovered a sudden liking for steel nationalisation. When useful, he supports the NHS as ‘free at the point of use’, but elsewhere peddles an ‘insurance-based’ model.

As Hope Not Hate testifies, far-right parties like Britain First mask the extent of their racism and misogyny whilst out canvassing, saving it for internal chat behind closed doors. Despite Reform’s cosmetic efforts, it continues to attract candidates with extreme right, often repulsively toxic views. Since Reform already struggles to publicly conceal its darker side, we shouldn’t assume the party will self-moderate. In power, it can let the mask slip and, supported by the global far-right, display extremist views openly. The parliamentary make up might obstruct some of Reform’s policies but it will still poison and degrade UK society.

Turning up the democracy heat

We all hope Reform’s incompetence is exposed quickly, and Starmer stops tacking right. But for effective action we should acquaint ourselves fast with our political landscape’s dangerous corners.

Points I’ve highlighted are that Labour may struggle to beat Reform, in particular, because -ideologically – their executives are too similar. If so, perhaps progressives should re-consider pushing Starmer to adopt more progressive policies and focus on raising public awareness about the far-reaching perils of Reform itself.

Related dangers are that our constitution isn’t inviolable; Trump isn’t an assured deterrent; our MSM is in thrall to Reform; and the far-right seeks to bend voters to their own ideology using all means available from camouflage to Big Tech.

Progressives often seem shocked at both the ease with which the far right can turn truth on its head, and how effective it is. We should stop being shocked and instead start acting predictively, creatively and strategically.

Claire Jones writes and edits for West England Bylines and is co-ordinator for the Oxfordshire branch of the progressive campaign group, Compass

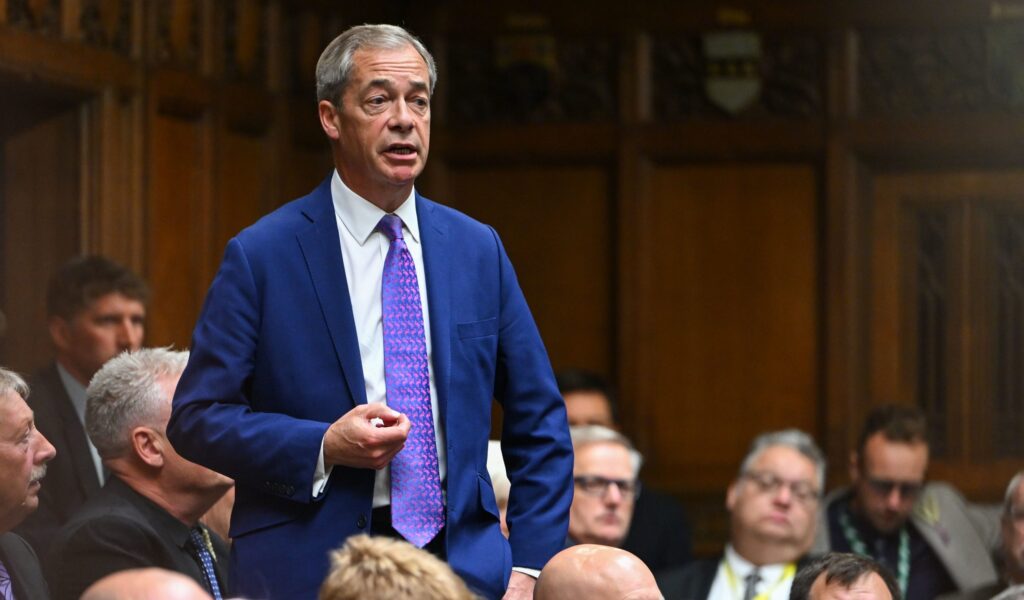

Image credit: House of Commons – Creative Commons

Left Foot Forward doesn’t have the backing of big business or billionaires. We rely on the kind and generous support of ordinary people like you.

You can support hard-hitting journalism that holds the right to account, provides a forum for debate among progressives, and covers the stories the rest of the media ignore. Donate today.