Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Technology sector myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

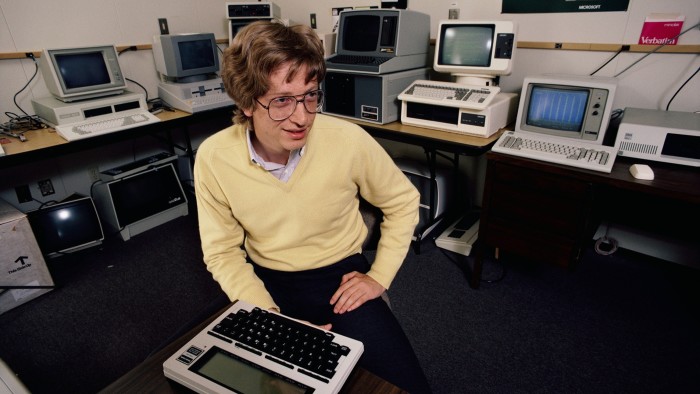

At an FT event a few years ago, Microsoft’s co-founder Bill Gates was asked what painful lessons he had learnt when building his software company. His answer startled the audience back then and is all the more resonant today.

Gates replied that in his early twenties he was convinced that “IQ was fungible” and that he was wrong. His aim had been to hire the smartest people he could find and build a corporate “IQ hierarchy” with the most intelligent employees at the top. His assumption was that no one would want to work for a boss who was not smarter than them. “Well, that didn’t work for very long,” he confessed. “By the age of 25, I knew that IQ seems to come in different forms.”

Those employees who understood sales and management, for example, appeared to be smart in ways that were negatively correlated with writing good code or mastering physics equations, Gates said. Microsoft has since worked on blending different types of intelligence to create effective teams. It seems to have paid off: the company now boasts a market value of more than $3tn and will celebrate its 50th birthday next year.

Gates may have learnt that lesson early. But while many of his fellow US tech billionaires share his original instinct about the primacy of IQ, few appear to have reached his later conclusion. There is a tech titan tendency to believe that it is their own particular form of intelligence that has enabled them to become wildly successful and insanely wealthy and to champion it in others.

Moreover, they seem to think this superior intelligence is always and everywhere applicable.

The default assumption of successful founders seems to be that their expertise in building tech companies gives them equally valuable insights into the US federal budget deficit, pandemic responses, or the war in Ukraine. For them, fresh information plucked from unfamiliar fields sometimes resembles God-given revelation even if it is commonplace knowledge to everyone outside their bubble. One young American tech billionaire, a college dropout who had just returned from a trip to Paris, once asked me with wide-eyed wonder whether I had heard about the French Revolution. It was incredible, apparently.

Inevitably, this leads to questions about the fungibility of Elon Musk’s IQ given his omnipresence in the US economy and now politics. The South African-born entrepreneur is blessed with an exceptional form of intelligence and clarity of vision that commands respect, even from his fiercest competitors. “I think he’s a fucking legend,” the chief executive of one rival electric vehicle company told me, even though he was personally appalled by the ways in which Musk had used his social media company X as a propaganda tool.

Although Musk excels at building cool cars and rocket ships, his personal brand extension into social media is flailing and he is facing a user and advertiser exodus at X. Still, Musk used the $44bn megaphone he bought to help elect Donald Trump. In turn, the incoming US president has now invited the “super genius” Musk to become one of two co-heads of the planned Department of Government Efficiency.

To cut bureaucracy, Musk is advertising for “super high IQ small-government revolutionaries willing to work 80+ hours per week on unglamorous cost-cutting”. Musk has already said he would like to axe three quarters of the federal government’s 400 departments. “99 is enough,” he posted.

These days, Musk prefers to troll Gates rather than listen to him. Yet he might still reflect on Gates’s painful lesson: the smartest people in one field do not always have the best ideas in others.

No doubt there is massive bureaucratic waste to be cut, but it will take many different types of intelligence to understand all the public benefits, competing agendas and conflicting interests surrounding government spending.

There is also a certain irony in tech billionaires trumpeting superior human intelligence when they are also developing AI that may one day overtake it. Google’s co-founder Larry Page labelled Musk a “speciesist” for defending human intelligence so doggedly in the face of advancing technology.

Naturally, Musk is working on a solution: he plans to upgrade our biological wetware using electronic brain implants developed by his company Neuralink to merge human and machine intelligence.

That prospect will terrify many but may, in a different way, prove the ultimate test of whether human IQ is fungible.