Here he burrows beneath a true story about a single punch that devastated multiple lives – and excavates multiple layers of resonance.

Toxic masculinity, class inequality, undiagnosed special needs, and the collapsing probation service all feed into Jacob Dunne’s story and the manslaughter of paramedic James Hodgkinson.

But it’s the aftermath of the punch outside Yates Wine Bar in Nottingham that’s the thread that binds a tale of forgiveness and redemption.

Director Adam Penford marshals a six-strong cast in multiple roles switching fluidly between naturalism and stylised movement sequences – between the before and after.

Julie Hesmondhalgh and Tony Hirst as the parents of victim James Hodgkinson.(Image: Marc Brenner)

Anna Fleischle’s set of concrete underpass and Canalside overpass both embody the Meadows Estate and the twin paths that Jacob might choose.

Angered by the light sentence for her son’s murder James’ mother – the brilliant Julie Hesmondhalgh – seeks restorative justice as a last ditch bid to deal with her grief.

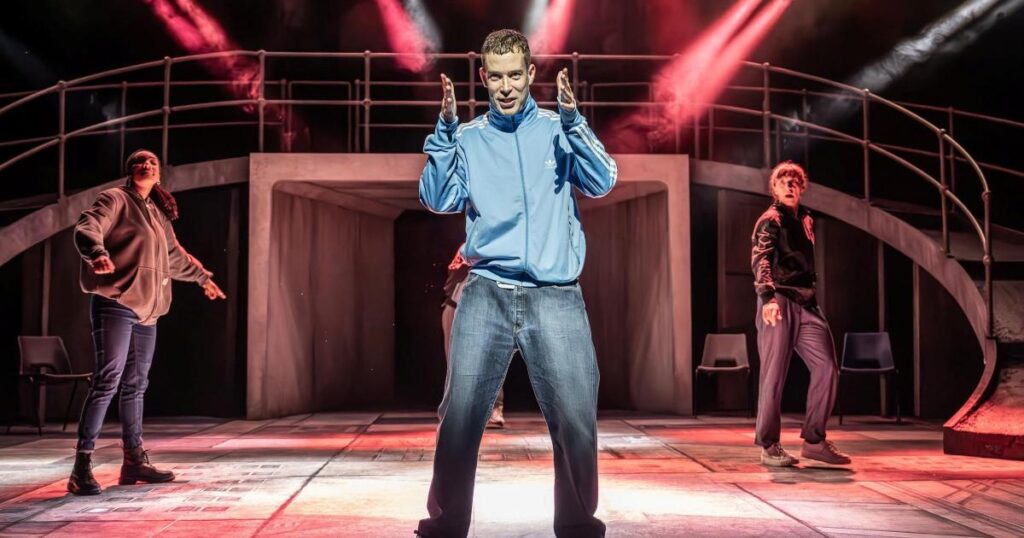

David Shields’ extraordinary performance as Jacob runs from cocksure teenage drug dealer ramapging on one fateful night out, to his first nervy night in jail, diagnosis with autism and dyslexia – and crippling recognition of his crime.

Graham brilliantly shows rather than tells us how group therapy, an overworked but empathetic social worker (a wry Emma Pallant) and the formal exchange of letters with his victim’s parents help to save Jacob from spiralling downwards.

In the programme, Graham describes theatre “as a restorative space of empathy and increased understanding,” and in unpacking the sadly common back story of an apparently thuggish youth and a senseless death, he ushers us away from prejudice.

After all if Hesmondhalgh’s Joan can forgive the man who killed her son then why can’t we? There’s a devasting stillness to her performance that left few dry eyes at her awkward meeting with Jacob – who goes on to gain a degree and write a book.

Many in the audience were accompanied by teenage sons – Punch is set in 2011 before the ubiquity of social media – so this pre-dates the toxic manosphere of the Tates.

But the kind of lad and gang culture aired here – of proving yourself to peers – remains all too relevant and the single punch death has sadly not gone away.

Punch runs at The Apollo Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue until November 29.