Rachel Reeves has confirmed she will change the UK’s fiscal rules in her Budget next week as she seeks to fund about £20bn a year of extra investment with increased borrowing…

Reeves is set to adopt a gauge called “public sector net financial liabilities” (PSNFL), according to people briefed on Budget discussions.

The gauge is a broader measure of the public balance sheet that includes financial assets such as student loans.

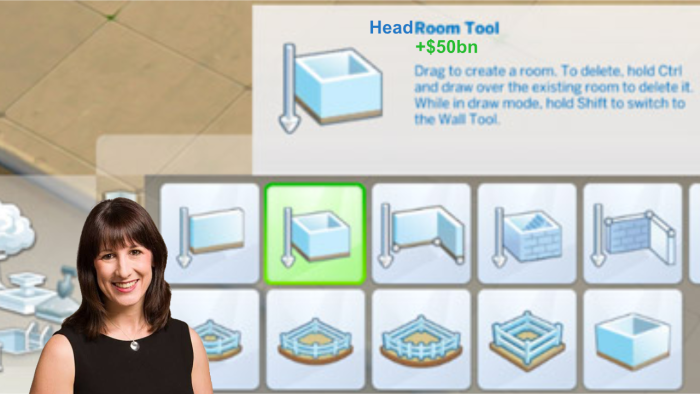

The change would give Reeves space to borrow an additional £50bn a year by the end of the decade and still have debt falling, under the Treasury’s March forecasts.

The £50bn figure is likely to change with new forecasts in the October 30 Budget and Reeves is not expected to access all of the potential borrowing, the people said.

Try not to fall off your chair in excitement.

First, links. Reeves’ piece is here, and the Guardian had the scoop on the tweak to PSNFL overnight.

We’ve been somewhat remiss in our duties by not writing about debt rules very much in the run-up to this Budget. It hasn’t been for lack of trying, more for an inability to read the ONS’s full notes on Public Sector Net Worth without descending into gibbering madness.*

What is (are?) public sector net financial liabilities, or PSNFL? Well, this (via the Institute for Fiscal Studies):

So that’s settled then.

Oh, right, the analysis.

In the scale of what Reeves could do without tweaking the core fiscal rules directly, this is moderately radical. Here, via RBC Capital Markets, is a précis of what it would mean:

PSNFL captures a wider range of financial assets and liabilities than recorded in PSND. Because the additional assets included in PSNFL compared with PSND exceed the extra liabilities included, it is lower than PSND. Again, crucially in respect of creating ‘fiscal space’, it is falling faster than PSND (ex BoE) and PSND over the forecast period including in the all important fifth year of the forecast (see Exhibit 2).

One main difference between PSND and PSNFL is funded pension schemes where not only are the pension liabilities but also are the financial assets held by those pension funds (non-financial assets are excluded). Other differences include loans, including the student loan book and the non-liquid assets held by the TFSME. Equity stakes in private sector companies held by the government are also included on the asset side of the ledger.

The main drawback of PSNFL as a fiscal target is the difficulty of valuing illiquid assets which may be difficult to dispose off. Another issue previously discussed by the OBR was difficulty of valuing pension liabilities, a feature that can cause significant revisions to estimates of PSNFL.

We say moderately radical: a switch to PSNFL would be a surprise, at least based on what the sellside expected.

RBC was far from alone in predicting the Chancellor would instead take a smaller step — switching to a target measure of public sector net debt excluding both the Bank of England and losses incurred via the Asset Purchase Facility through which the UK’s quantitative easing programme operates (FTAVs passim here, here, here).

Here are JPMorgan’s Allan Monks’ words and table, from late September:

It would be very risky for Labour to fully abandon a more conventional debt target, and we expect a more measured approach as it seeks to lift investment spending…

…even with a more explicit recognition of the benefits, it would still be risky for the government to simply shift solely to a measure that excludes the impact of investment spending. Option 7 in the table below estimates £60bn of “headroom”, with Option 5 freeing up £50bn. This is large enough as it is. But it should be stressed that as investment is effectively excluded from both of this net concepts, there is actually no clear limit for that particular form of spending under these rules. Likewise, Option 6 could in theory allow almost limitless spending if done under the guise of the National Wealth Fund.

✨ “Almost limitless spending” ✨… where have we heard that one before?

OK, we’re not seriously suggesting that Reeves is about to go completely buck wild on spending. Learnèd commentators point out that opening up £50bn of headroom then NOT using it is one way of helping ‘future you’ without sPoOkInG tHe BoNd MaRkEt. And Reeves setting out the stall for just £20bn of borrowing within this new space is a clear attempt to signal restraint to markets.

Will it work? Here’s Société Générale’s Sám Cártwríght, in a note dated yesterday that landed in our inbox, somewhat unfortunately, this morning (ie post-Graunscoop):

A possible change to the debt rule is more contentious. The Chancellor has stated “it will be a budget for investment”. However, the current debt rule offers no room for additional borrowing to fund capital spending. We believe a shift in the debt rule to target public sector net debt (PSND), unlocking an additional £20bn/year in capital spending, is the most likely option. Additional borrowing above this figure could spook the markets, making a more radical shift to public sector net financial liabilities (PSNFL) less likely. Overall, the budget is likely to be a fiscal loosening vs the current plans due to the increased borrowing to fund capital spending…

All in all, the risk of spooking the markets and causing another Liz Truss-style meltdown will be playing on her mind, which we believe makes a move to PSNFL unlikely. However, we wouldn’t rule it out entirely. The government could switch to targeting PSNFL and cap borrowing to around £20bn/year.

🎯

Oxford Economics’ Michael Saunders (also base-casing APF exclusion) shared those latter sentiments in a note published earlier this month:

If the Chancellor does shift to a PSNFL target, we expect she will use this fiscal space relatively cautiously. For example, she could aim to retain much greater fiscal headroom against the fiscal rules than recent Budgets and shorten the timeframe to achieve a falling debt ratio from five years to three years. Assuming any extra current spending after this year is fully offset by tax hikes in the Budget, a PSNFL/GDP target with greater headroom and a 3-year horizon would allow a substantial rise in public investment to 3% of GDP in 2028/29, about £40bn above the March Budget plans.

So — a bit radical, a bit of a shift, but also nothing unpredictable. The big wheel of UK economics keeps on turning.

Well, there are always dangers. Barclays (their emphasis):

PSNFL would also affect incentives for off-balance sheet structures to promote investment/spending as they would alleviate constraints of the primary fiscal rule. Under PSNFL, borrowing to invest in building a road or a hospital would not be constrained by the secondary fiscal rule, but would reduce the headroom against the primary fiscal rule. However, if the government were to borrow to lend to an off-balance sheet vehicle that then spent the same money on the same project, the loan to that off-balance sheet vehicle would count as an illiquid financial asset and be netted against the additional borrowing. This would mean the reduction in headroom was less, or even zero. This raises the prospect of a change back to a “PFI-type” world of the early 2000s, where gilt borrowing increases in order to onlend funds to off balance sheet entities which then lend/invest in public projects. Crucial to this will be the ONS’ assessment and classification of any vehicle as it requires them to determine that the government is sufficiently arms-length in the extent of control it exerts.

Hmm. Can anyone remember how that went last time?

Further reading:

— ‘Toxic’ relationships, shouting and lawsuits: the bitter end to Britain’s PFI experiment

Update 5pmish BST: Little update with a nice graph from Deutsche Bank putting today’s gilts underperformance (thus far) in context:

*Q: What’s the UK public sector worth?

A: As of June, just shy of -£700bn. Yes, minus.

That’s according to the latest Office for National Statistic calculations (at the bottom of section 7 here; fresher but less resolvable figures up to September are here), which found that for the second quarter of the year the UK’s various public bodies —

— had about £3tn of assets, and £3.7tn of liabilities. The balance of these two numbers is Britain’s PSNW (in accordance with the European System of Accounts 2010 framework), a figure that’s been bouncing about for a bit over a decade.

Two big problems with PSNW itself, all of which presumably come up if the UK ever did consider adopting it as a target:

-

There are three different versions of PSNW — the ESA (shown above) and IMF versions, produced by the ONS, and the Whole of Government Accounts version that the Treasury produces with a longer lag, all of which cover slightly different things.

-

Valuing future assets is hard, like really hard.

ESA PSNW, as befits a number that covers everything from local council loans to National Gallery Holbeins, is a big, fuzzy statistic — one requiring so much caveating that the ONS’s breakdown includes £940bn of “consolidation” on the asset side, and £850bn on liabilities.

With those adjustments in place, the underlying statistics require absurd caveating, but do let us create rubbish diagrams like this:

Having prodded around with that for a while, you will have learned almost nothing that is useful.