Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

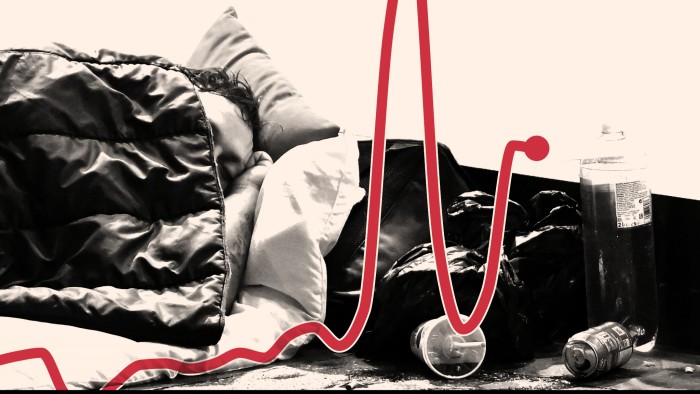

Efforts to clear the backlog of asylum applications risk creating another wave of homeless refugees as those granted protection are told to leave government-rented hotels, experts have warned.

The Home Office is speeding up the processing of asylum applications, it announced this month, in a bid to reduce the costly reliance on hotels, which have become the target of violent anti-immigration protests.

When the previous Conservative government tried to clear the asylum-application backlog in 2023 it led to a surge in people granted refugee status but was also followed by a sharp rise in households owed a “homelessness duty” by a local council after losing Home Office-provided accommodation.

The figure, which refers to refugees who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless after leaving Home Office accommodation, rose to a record 7,160 households in the last quarter of 2023 and has since only fallen slightly, to 5,940 in the first quarter of this year, according to government data for England. Meanwhile, overall homelessness is close to a record high.

Bridget Young, director of Naccom, a network of charities that help refugees and asylum seekers with housing, said there was a “real and pressing concern” that the 2023 surge in homelessness would be repeated under the government’s current approach to asylum processing.

Jacqui Broadhead, director of the Global Exchange on Migration and Diversity at the University of Oxford, said the Home Office would need to work closely with local authorities to communicate when decisions are made “to try to avoid high numbers of newly recognised refugees presenting to council homelessness services at the same time”.

The push to clear the asylum-application backlog is likely to have a knock-on effect on local councils that have a duty to house the homeless but are also under pressure from a severe shortage of social homes and rising private rents. Just under half of applications for asylum were granted last year, although this figure does not include dependants and the eventual rate will be higher once appeals are accounted for.

“What puts [council] housing services under real strain is often not only the overall number of refugees but getting a lot of grants in a short amount of time,” said Broadhead.

The topic has risen up the political agenda because of the soaring number of people arriving in the country on small boats — this week the figure reached 50,000 since Labour came to power — and as the anti-immigration Reform UK party performs well in opinion polls. The government has responded with a series of policies, including cutting spending on asylum seeker hotels and a deal with France to send back small-boat arrivals.

The total number of households receiving short-term homelessness support reached 83,450 in the first quarter of 2025, only 6 per cent below the record high in the first quarter of 2024. This figure does not include an estimated 7,718 rough sleepers, as of March 2025. There were 1.33mn households on council housing waiting lists as of March 2024.

Areas with asylum hotels are at risk of coming under the most pressure as refugees usually have to seek support in the same area as their Home Office accommodation.

The government has tried to mitigate this by spreading asylum seekers more evenly across the country and piloting a doubling of the time, to 56 days, that people granted refugee status are allowed to stay in their Home Office-provided accommodation while they try to find somewhere else to live.

But many refugees end up homeless as they cannot work until they are granted asylum and most homelessness services only help people on “the edge of crisis”, said Broadhead, who called for them to be given better support to find a job.

Young said it was “vital” to recognise other drivers of homelessness, which also included the freeze on housing benefit, a lack of social housing and rising rents. “Refugees are disproportionately affected, but they’re not the only ones falling through the cracks,” she said.

Mairi MacRae, director of campaigns and policy at Shelter, said “spiralling” homelessness rates were caused by a severe shortage of social housing and “runaway” rents. She said that asylum seekers should not become “scapegoats” for a political failure to deliver affordable homes: “If net migration was zero, we would still have a housing emergency.”

She called on the government to increase social housing construction to 90,000 a year for 10 years “to end homelessness for good”. Some 10,153 social-rent homes were built in England in 2023-24.

The Home Office said it would “continue to work with local councils, NGOs and other stakeholders to ensure any necessary assistance is provided for those individuals who are granted refugee status to get ready for life outside of asylum accommodation”.

It added: “It does take time to turn the chaos we inherited round, but our plan will cut asylum accommodation costs, and end the use of asylum hotels by the end of this Parliament.”