A judge has raised questions over whether a top investment bank was harmed by a rainmaker’s alleged plot to start a rival firm, as the messy dispute reaches its end in a New York courtroom a decade after it first gripped Wall Street.

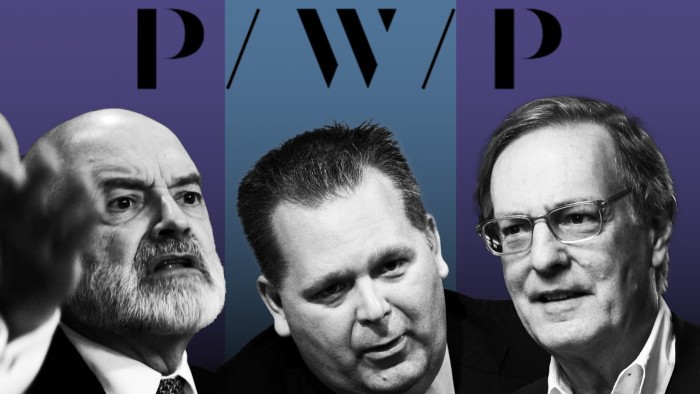

Perella Weinberg Partners, a well-regarded M&A advisory specialist, has asked the court to award it tens of millions of dollars from Michael Kramer, the former founding head of its corporate restructuring segment.

The bank accuses Kramer of improperly coaxing seven PWP colleagues to join a rival bank he would eventually create. Kramer formed Ducera Partners in 2015 with nearly all of the existing senior bankers in PWP’s restructuring group. Kramer is seeking to recover more than $40mn in equity that the firm seized upon his termination, out of the nearly $100mn in total pay he accrued at PWP over a seven-year stint.

PWP, for its part, is seeking $40mn in damages stemming from the cost of hiring replacement bankers and the bonuses it paid to Kramer and his dissidents around the time of the terminations.

Judge Robert Reed of the New York Supreme Court told lawyers from PWP on multiple occasions that employment law is sceptical of so-called restrictive covenants, which dictate how bankers can leave and start competitive ventures. He said the bank, to be reimbursed, had to demonstrate that the impact of any improper solicitation by Kramer was different from a scenario in which the departing bankers followed the letter of their restrictive covenants.

“I think it’s important that you understand that PWP, as plaintiff, has to show that the damages that they seek to recover were not self-inflicted,” Reed told each side’s lawyers.

The trial has forced both PWP and Kramer to reveal in public the typically shrouded practices of investment banking. Peter Weinberg, PWP’s co-founder, told Kramer in the months prior to his termination that while he was valued as a rainmaker for the firm, he “repelled” his colleagues with what he testified was a difficult personality.

The court heard that PWP executives wanted to keep Kramer but struggled with how to convince him to stay given the firm’s decision that he not have a top managerial role. In any case, Kramer found their efforts unconvincing.

“I don’t think you tell somebody you’re not going to have a future at the firm, and then not think that they are going to potentially want to leave,” Kramer testified.

Kramer denied he had enticed colleagues to join a new firm. He told the court he had been considering retiring from PWP to, among various options, purchase a farm or spend time on his winery. He said he implored colleagues to remain at PWP.

Evidence presented to the court, however, showed that detailed strategic plans and spreadsheets for a hypothetical firm were exchanged through emails among several restructuring bankers and sometimes when Kramer was present. Kramer testified that he often did not read his emails and that any planning for a new firm — which included work with a branding consultant — was driven not by him but by junior colleagues.

“I don’t mean to sound arrogant, but I’m pretty busy,” Kramer told the court. “So I selectively go through what [emails] I should look at.”

Judge Reed left open the possibility that Kramer could be found to have violated the non-solicitation clause, a contract violation that could allow PWP to keep the equity Kramer was suing to recover.

“You have a higher obligation from Mike Kramer to say to the young people, look, if you guys are dissatisfied, I understand that but I can’t be involved in anything like this,” Reed told the lawyers.

Even among the banking luminaries who took the stand, the most anticipated witness proved to be Kevin Cofsky, a mid-level banker on Kramer’s restructuring team awaiting a partnership promotion at the time of the 2015 upheaval. Cofsky would go on to cast his lot with co-founder Joe Perella while most of the other key members of the restructuring group were considering leaving with Kramer, as the two had bonded, in part, over a love of college wrestling.

However, PWP demanded that Cofsky demonstrate his loyalty by sharing the details of the restructuring group’s alleged efforts to launch a new firm, the court heard. Within 72 hours, Kramer and three of his deputies had been fired via voicemail without ever being asked by the firm for their side of the story, Weinberg confirmed in his testimony.

“I was very uncomfortable and anxious about what I had done,” Cofsky testified. “I felt bad . . . I worked with Mike for a long time.”

Cofsky said that in the years after committing to PWP he was promoted to partner and his annual pay jumped from $1mn to nearly $5mn.

The terminations during the 2015 President’s Day weekend proved chaotic as Weinberg and then-chief executive Robert Steel were on separate ski trips in Colorado. At one point, Steel wrote in a message to Weinberg that he would be unreachable while he was “off to ski” for several hours as Weinberg was finalising the terminations.

Emails shown to the court also revealed that PWP emphasised winning the narrative battle over the Kramer sacking among its clients, remaining employees and the broader public.

Emails from Perella to other PWP executives mused about “going the Sorkin route” — a reference to leaking an internal memo announcing the Kramer firing to the New York Times journalist Andrew Ross Sorkin, who was friendly with Perella. The memo contents did appear in the New York Times, though PWP executives denied they had supplied it to the newspaper.

A few months after the terminations, Weinberg instructed the PWP communications chief in an email to deny to The Wall Street Journal that the Kramer group departures were hurting the firm’s results. Kramer’s lawyers pressed Weinberg about the inconsistency between the response to the 2015 newspaper article and the current lawsuit which claims their client committed $40mn worth of harm to PWP.

PWP’s contempt for Kramer was acute enough that the firm terminated two of his existing restructuring advisory mandates, drawing the ire of those clients. Marc Rowan, the founder of Apollo Global Management, wrote in vain to Peter Weinberg in 2015 that “PWP needs to be an adult and put the client first”, in an effort to keep Kramer on the bankruptcy of Caesars Entertainment.

An executive of Monsanto testified that Weinberg refused to allow Kramer to continue advising the company’s board on a possible $50bn tie-up with Syngenta, a move that shocked the chemicals titan.

“We felt that [PWP] were damaging us. They were taking away the trusted adviser to our board and trying to put themselves in the driver’s seat,” testified David Snively, the former Monsanto general counsel.

The court is expected to issue its written opinion over the next few months.

It was left to 83-year-old Perella, whose ownership stake in PWP far exceeded Weinberg’s, to tell the court how the world of high finance had changed since 1988, when he famously started his own boutique firm within hours of resigning from First Boston Corporation.

“When I resigned from First Boston, there were no written agreements . . . And I think people woke up and decided, well, we can’t let this happen to us,” Perella said.

“So they started tying people down with lockups and whatnot. But that’s the world of today; that wasn’t the world in ‘88.”