Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

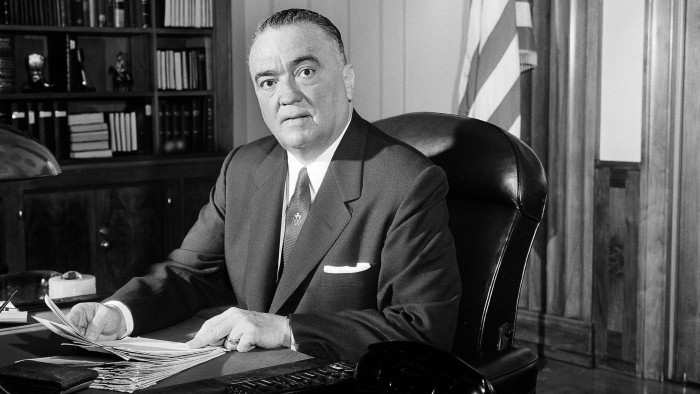

British secret agents in Washington requested that J Edgar Hoover’s honorary knighthood be listed in the who’s who almanac Debrett’s to placate the FBI head, previously classified documents show.

The correspondence — which show how British officials worked assiduously to maintain the UK-US special relationship after an embarrassing spy scandal — were among archives of the MI5 domestic intelligence agency unlocked on Tuesday.

The released documents also give fresh details about the “Cambridge Five”, the cold war Soviet spy ring of UK agents that damaged Hoover’s faith in the British secret service.

The National Archives in Kew periodically publishes declassified files released to it by MI5. The latest release comes only a week before the inauguration of Donald Trump, who has nominated an FBI director who proposed rebranding the agency’s headquarters as a “museum of the deep state”.

Kash Patel, Trump’s nominee, is a graduate of University College London and has previously said the US has “no better ally than the UK”.

Current MI5 chief Ken McCallum last week praised the outgoing FBI head Christopher Wray and the close working of the two agencies, saying he looked “forward to working with his successor as our organisations continue to strive to keep our great nations safe”.

The documents unlocked on Tuesday reveal an episode from 1951 in which British officials on both sides of the Atlantic acted to placate Hoover.

He had been given an “honorary knighthood” the previous year to soothe his hot temper after it emerged that “atom spy” Klaus Fuchs, a UK citizen, had leaked nuclear secrets from the Manhattan project to the Soviet Union.

The knighthood ploy seemed to work. The honour, which is for non-UK subjects, was awarded at a simple ceremony at the embassy in Washington, and Hoover wrote to the head of MI5 in London saying it had “deeply touched” him and mentioned that he had asked for his appreciation to be “conveyed to His Majesty”.

However, Geoffrey Patterson, the MI5 liaison officer in Washington, wrote to colleagues in London on November 8 that he had heard that Hoover was disappointed not to find his knighthood listed in Debrett’s, the almanac of Britain’s titled aristocracy.

Patterson’s cable said Hoover had checked the Washington embassy’s copy of Debrett’s, only to find “no mention of Sir Edgar!”

Eleven days later, London cabled back a curt two-paragraph memo, marked “CONFIDENTIAL”, even though it dealt with protocol rather than active intelligence.

The next edition of Debrett’s would be published in the spring of 1952, and “for the first time” would contain mention of honorary knights, it said, adding: “I am assured that Mr Hoover’s name will appear.”

The importance of the special relationship is an enduring theme in this release of historic MI5 papers, which run from the 1940s up to the 1970s, and some of which will be on show at Kew’s National Archives in an exhibition this year titled “MI5: Official Secrets”.

In another dispatch sent to London, Patterson stressed that “he [Hoover] told me . . . that he was well aware of the importance of maintaining the closest collaboration between the two organisations”.

The released papers also include a full transcript of the 1964 confession by Anthony Blunt, who worked for many years as the Queen’s surveyor of the royal pictures while also spying for the Soviet Union.

Blunt’s identity as the so-called “fourth man” in what became known as the Cambridge Five was only publicly revealed in 1979 by Margaret Thatcher — although Edward Heath had instructed that the Queen be given a detailed report about her courtier six years earlier.

But the papers also include an indication the Monarch may have already known about Blunt. A document marked “TOP SECRET” and dated March 19 1973 reads: “She took it all very calmly and without surprise . . . Obviously, somebody mentioned something to her in the early 1950s, perhaps quite soon after her accession.”

The documents also feature the dramatic-but-bogus confession of Kim Philby, the head of British foreign intelligence in Washington who was also a Soviet spy and one of the Cambridge Five.

Philby’s six-page, typed confession begins with the words that “it is the best of my knowledge true in all particulars.” It was, however, full of lies, including Philby’s claim that Blunt “did not, and would not have, worked for the Russians”.