Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

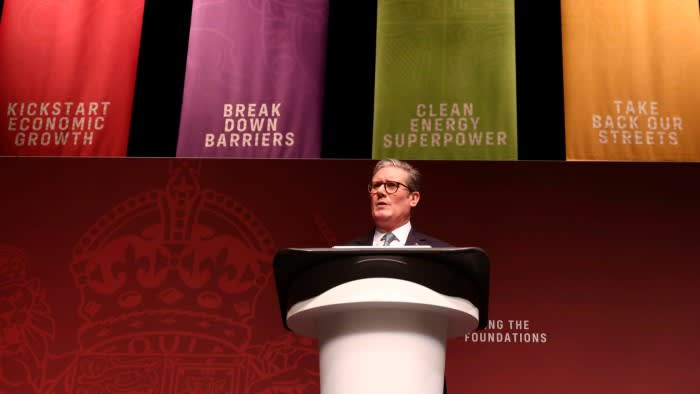

Sir Keir Starmer has said he cannot rule out further tax-raising Budgets after his administration’s maiden fiscal event on Wednesday, in which he said Labour would “run towards the tough decisions”.

The UK prime minister said that “nobody wants tax rises, least of all me, so we will do the hard work in this Budget” in order to rebuild the country, as he raised the prospect of significant increases.

However, he told an audience in Birmingham that “I can’t give you a cast iron guarantee that never again in any Budget will there be any adjustment to tax because we just don’t know what’s round the corner”, as he cited the Ukraine war and Covid-19 pandemic as examples of unexpected surprises.

Speaking on Monday in his final pitch to the public two days ahead of the Budget — Labour’s first in almost 15 years — Starmer said his international investment summit earlier this month was a “proof point” that investors had confidence in his agenda.

The Budget is expected to contain up to £40bn of tax rises and spending cuts along with extra borrowing of about £20bn a year to fund investment in the NHS, schools, green energy and transport projects.

Starmer also argued that his government’s plan to borrow more for capital expenditure would not push up interest rates.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves confirmed last week that she was rewriting the fiscal rules to include government assets in the UK’s measure of debt. She is expected to fund about £20bn a year of extra investment with increased borrowing facilitated by this move.

Yields on government debt have risen in part because of concerns about higher borrowing. The benchmark 10-year gilt yield climbed as high as 4.29 per cent on Monday, its highest since early July, before slipping back later.

Former Tory chancellor Jeremy Hunt has said the “consistent advice I received from Treasury officials was always that increasing borrowing meant interest rates would be higher for longer”, writing on X that such a move would “punish families with mortgages”.

Starmer told the Financial Times he was determined to invest in better jobs and infrastructure, which was part of his plan to “rebuild the country”, but added of his borrowing-fuelled investment plan: “I do not accept the proposition it will have an impact on interest rates.”

He said Labour would “embrace the harsh light of fiscal reality” to move Britain off a path of decline, but he was facing growing criticism that planned tax rises would hit the “working people” he had pledged to protect.

He declined to offer more detail about the categories he believed fell within the definition of “working people”, following his suggestion that landlords and owners of shares did not count.

Insisting that “the working people of this country know exactly who they are”, he said workers were “the golden thread that runs through our agenda”.

But Reeves is facing strong criticism over her plan to increase employers’ national insurance contributions by up to £20bn, a tax rise that economists say will be passed on to workers through lower wage increases.

Hunt said the rise in employer national insurance contributions was a backdoor way of clawing back his pre-election £20bn cut in employees’ national insurance contributions.

Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies think-tank, said it was “essentially undoing the cut”.

Starmer outlined his priorities for the Budget as being stability, investment and reform. He has announced £240mn in the Budget to provide local services to help people back into work “and the dignity that that brings” as he vowed to create a “Britain that works for working people — with all those who can playing a part”.

The government would be “ruthless” in clamping down on Whitehall waste and tax avoidance in order to help repair the public finances, he added.