The way private equity executives have been able to amass vast personal fortunes has been a source of admiration and contention for years.

At the heart of what Oxford university professor Ludovic Phalippou has controversially described as the “billionaire factory” is carried interest, the share of profits that buyout fund managers receive when they sell investments.

Also called “carry”, it is a regular political flashpoint in the US, the EU and currently the UK, where the sector is awaiting the outcome of a tax consultation by the newly elected Labour government.

Why is there a debate over carried interest taxation?

Carried interest has enabled a lot of private equity executives to become very wealthy within a few decades, as buyout firms from KKR to CVC Capital Partners rode an era of cheap debt to fund investments and boost returns. Carry distributions to individual dealmakers can dwarf the salaries that firms pay using management fees — the steady income these receive on committed buyout funds, typically levied at a rate of 1.7 to 2 per cent.

Globally, private capital firms have earned more than $1tn in carried interest since 2000, according to Oxford university research published earlier this year. Blackstone Group, the world’s largest private equity group, has earned $33.6bn in carried interest alone since then.

In the UK, a Treasury analysis showed that 3,000 dealmakers shared £5bn in carried interest in the 2022 tax year — or £1.7mn each on average.

Carry is typically treated as a capital gain, and taxed at a lower rate than income. Many buyout managers argue this is legitimate because they invest some of their own capital alongside their outside investors — the so-called limited partners in a fund.

But critics — among them a few insiders and prominent financiers — say that carry, which is typically 20 per cent of a fund’s gains after a minimum return is met, is not proportionate to the capital that the firms and executives put at risk. That figure is on average just 4 per cent of total funds globally, with the median being just 2 per cent, according to Preqin.

Because of that, these critics argue that carried interest is more akin to a performance fee and should be taxed as income.

How is carried interest structured?

There is huge variation in how carried interest and management fees work across firms and asset classes. Typically, buyout firms set up funds that in turn invest in companies. They hold these companies for a few years before reselling them with the aim of multiplying their initial investments (a return of over 20 per cent a year is usually what is marketed).

Executives at four large European and American firms said they expected their individuals to co-invest.

But it is widely recognised that at some groups, individuals are not required to co-invest their own money to be eligible for a share of the eventual profits as carried interest.

Authorities in countries such as the UK, US, Spain and Germany also do not currently require a co-investment by individuals to levy carry at a lower rate than the ordinary income tax rate.

In the UK, the firm or its executives might pay token amounts into the carry vehicle for tax purposes. On a £100mn fund, for example, it might be £2,500 between 30 people, according to one leading funds lawyer.

These token carry payments are another driver of the controversy surrounding the current taxation of carried interest as a capital gain in the UK.

“Nothing material is paid for the carry,” the lawyer added.

Private equity executives argue, however, that their co-investment — which is separate to the UK token carry payment — is a prerequisite to the fund existing at all.

“If we don’t invest that amount, there is no fund,” said a top executive at a large European private equity firm, which requires its individuals to co-invest.

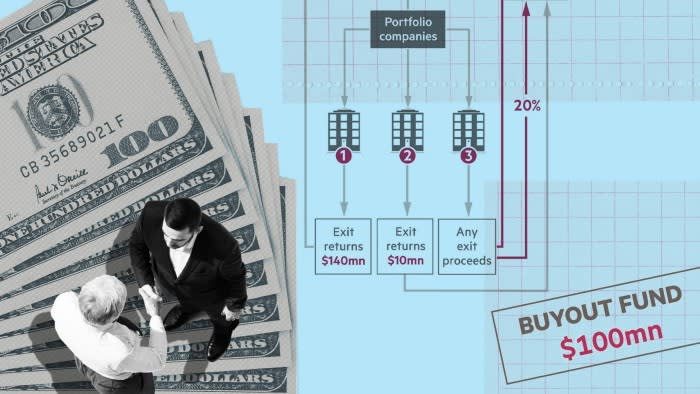

Before it can share any profits with the private equity firm or its executives, the fund must return to investors their drawn capital and a minimum return called the “preferred return”, usually worth about 8 per cent per year.

Any co-investment made by the executives or the firm will be treated similarly to investments by external LPs.

Co-invest vehicles tend to receive a share of the fund’s profits in line with what they originally put in, which they can then divide among their participants. This is not carried interest.

Then, the carried interest recipients typically get all of the next distributions until they have “caught up” and received 20 per cent of all fund profits distributed by that date.

Any profits distributed by the fund after that are shared 80:20 between the LPs and the carried interest recipients.

In a simplified example, if a $100mn fund bought three companies on day one and the first exit returned $140mn after five years…

This example shows what is known as a typical “European waterfall”, which only allows carry to be distributed after the original cost of all investments and the preferred return on such investments has been paid to investors.

US firms tend to follow a different structure, known as the “American waterfall” — though some European firms adopt a version of it.

Rather than wait until the cost of all investments has been paid back and the preferred return paid out, American waterfall funds distribute carried interest on a deal-by-deal basis.

This structure means a fund could pay out carried interest after selling its first portfolio company — provided that it makes enough from the sale to cover the original cost and preferred return on that investment.

But if later exits mean there are not enough proceeds to cover the preferred return on the fund as a whole, investors can often “claw back” some or all of the carry that has already been distributed.

How is carry distributed?

The approach to who is entitled to receive carry is a reflection of where the ultimate power lies in the firm, especially when it is not publicly listed. While it differs between firms, carry is often concentrated on a small number of top dealmakers.

Sometimes the way carry is divided up between executives will have been fixed at the start of a fund. But the split is sometimes determined based on how they have performed — or a mix of the two.

People who leave the firm sometimes have to forfeit their right to carry, but other firms allow them to remain invested and receive their share.

One executive at a large European firm said every employee, even in the IT and HR departments, was able to invest to receive carry, while their counterpart at another group said only partners participated.

One said around 30 people shared carry; a partner at another firm said their total tended to be closer to 100.

At EQT, the Swedish listed buyout group, carried interest is usually split 35:65 between the firm and its professionals based on their investments.

Applying an illustrative example that EQT gives in its annual report to the €22bn private equity fund it raised recently, if the fund achieved a gross return of two-times invested capital, that could translate to carried interest of €1.4bn for the firm and €2.5bn for EQT individuals.

Funds of such scale are outliers, but if the same multiple of returned capital, fees and expenses was applied to a $200mn private equity fund — closer to the global median size last year — a buyout firm would receive $35mn in carry to share between the house and its professionals.

alexandra.heal@ft.com