Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In the decade after the financial crisis, the parties of the European centre-left all had a similar nightmare: that they would be supplanted and replaced by new parties, whether on their right or their left. This nightmare had a name: Pasokification, after the fate of the Greek social democrats (although that particular party has since turned out to be happy, healthy and alive).

Now a similar fear is gripping the world’s centre-right. It doesn’t yet have a name, but one appropriate label might be “Pécressification”. When Valérie Pécresse became the French centre-right’s standard-bearer in the 2022 presidential election, she was hailed as the “woman who could beat Macron”. Instead she excelled only in self-destruction. She oscillated, uneasily and unconvincingly, between trying to win votes from Macron and from Marine Le Pen. In the end she simply gave away votes to both candidates and finished fifth with less than 5 per cent of the vote.

Or perhaps we could call it “DeSantis Syndrome”. After the Democrats outperformed expectations against Maga candidates in the 2022 midterms, Ron DeSantis was hailed as the future of the Republican party. Instead, the Republican party’s future turned out to be its past, and DeSantis lost, in a landslide, to Donald Trump. DeSantis, unlike Pécresse, did at least make a clear choice on which way to pitch his campaign, but unsurprisingly “Donald Trump is wonderful, don’t vote for him” failed to make much headway.

There are other, less fatal cases of Pécressification: Germany’s Friedrich Merz is on course to win the looming German election and to form a government. But his big political argument to his party was that by moving to the right, the CDU could peel off votes from the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and escape from the soggily centrist coalitions that Angela Merkel ran for most of her tenure. It hasn’t worked: the AfD is stronger than ever and his prospects for avoiding another centrist coalition are not good.

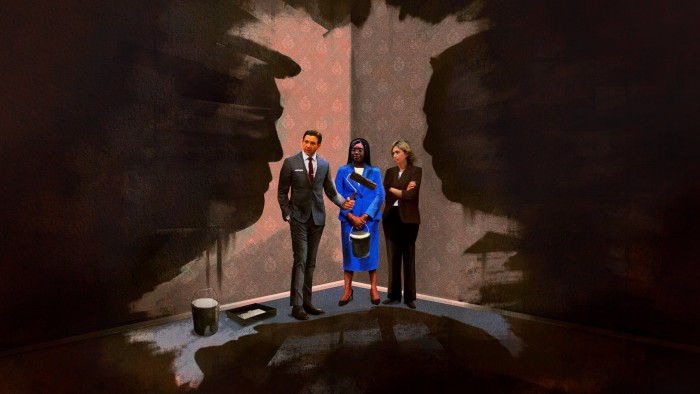

UK Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch is the latest politician from the mainstream right to try to succeed by emulating her rightward challenger. In a week in which the British economy sputtered and a government minister was mired in scandal, she chose to focus on calling for a fresh national inquiry into the grooming gangs scandal despite the fact that neither she, nor her front bench, had much of a grip on the details. Her team kick-started their campaign by calling on the government to release data that had already been made public in November, and it went downhill from there.

Unsurprisingly, voters are not convinced. A poll this week found that just 18 per cent of British voters trust Badenoch on the issue, below Keir Starmer and Nigel Farage. And why would they? She did not advocate another inquiry when she was a cabinet minister. She did not call for one in her leadership bid, and indeed does not even appear to have noticed the latest developments. Starmer and Farage have wildly different perspectives and motivations, but you can’t fairly accuse either of them of being unaware of the scandal.

Badenoch is struggling for the same reason as DeSantis and Pécresse: she has chosen to fight Farage on the ground where he is strong and she is weak. If you think that the last Conservative government was a meek failure, why would you vote for one of its power players when you could vote for an insurgent whose reputation has never been sullied by government or its compromises?

Her chosen strategy has not worked for anyone else on the mainstream right and there is no reason to believe it will be any more successful when she tries it. Indeed, there are good reasons to believe it will work less well. There can be few more unconvincing fixer-uppers to remodel as an anti-system party than the Tories, the most successful centre-right party in Europe and one of the oldest in the world.

But Pécressification is a problem for everyone, not just parties of the old-school right. No one in the French centre or on the left can, with a straight face, say that it would not be better if Pécresse had won out over Le Pen. Certainly the Democratic party would prefer that DeSantis were president and not Trump. And anyone of a moderate disposition ought to hope that Badenoch remains the face of the British right and not Farage. But the centre and the left cannot imbue the centre-right with a willingness to fight to preserve its distinctiveness in the face of populist challenges. The fate of the Conservatives ultimately hinges on whether Badenoch decides her party’s values and unique identity are worth fighting for.