This article is an on-site version of our Inside Politics newsletter. Subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday. If you’re not a subscriber, you can still receive the newsletter free for 30 days

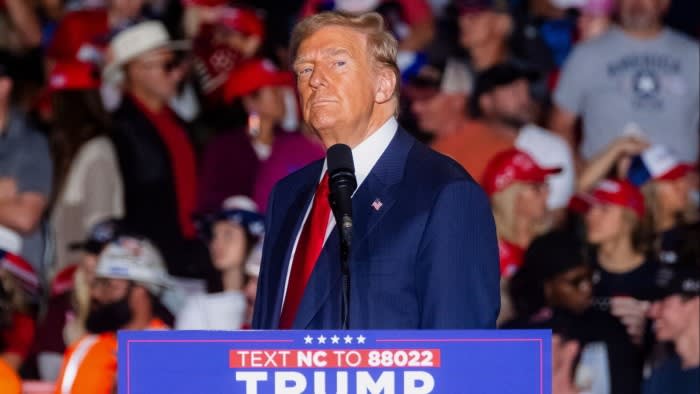

Good morning. We have the first diplomatic row of the new Labour government: after Donald Trump accused the Labour party of interference to help Kamala Harris in the presidential election:

The complaint filed by Trump’s campaign to the independent Federal Election Commission accuses the Labour party of sending strategists and staffers to help the Democratic presidential candidate’s election campaign and says Harris has accepted the help. Keir Starmer, however, defended the aides, saying they were volunteering in their spare time.

The prime minister referred to the idea of Labour volunteers going over for pretty much every US election as “straightforward”. More on that below.

Inside Politics is edited by Georgina Quach. Read the previous edition of the newsletter here. Please send gossip, thoughts and feedback to insidepolitics@ft.com

Technically correct, the best kind of correct

An inevitable consequence of being the most important democracy in the world is that outsiders will take a major interest in your elections. Just as we now watch elections in the US, the world elsewhere once did for the UK. Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi listened to the results from the 1945 election and hoped that Clement Attlee, who they knew well from the 1930s and wartime period, would win the election, because they thought that he would make a better negotiating partner than Winston Churchill.

In 1964 Kenneth Kaunda, later to become Zambia’s first president, listened to the outcome of the UK general election and cheered every result “as if it were for the United National Independence Party [Kaunda’s party]”. (Though, as it happens, Kaunda would swiftly be disillusioned by Harold Wilson, who led Labour into its 1964 election victory, and the former British prime minister’s handling of Rhodesia’s unilateral declaration of independence.)

Global power has long since decisively shifted to Washington and now it is American elections that the world watches with bated breath. It’s long been a tradition for Labour to learn from the Democrats and vice versa. Kamala Harris uses the same phrase — “turn the page” — that Labour used in July, just as Tony Blair’s “New Labour” aped Bill Clinton’s “New Democrats”.

A similar dynamic holds across the democratic world. I often meet Conservative or Labour strategists who have honed their skills learning from sister parties in Canada, New Zealand, Australia or the US. Robert Jenrick talks frequently of the lessons that the UK Conservatives can glean from Pierre Poilievre, leader of the Canadian Conservatives.

There are plenty of strategists who have fought and won elections for centre-left and centre-right parties across the English-speaking world: Stan Greenberg on the left, Isaac Levido on the right, Lynton Crosby, and so on.

So Keir Starmer is wholly correct when he says it is normal for Labour party staffers and former Labour party staffers to volunteer their own time in US presidential campaigns.

But the big and important difference now is that Donald Trump is a very different kind of politician. In the unlikely event that Poilievre loses the next Canadian general election, Justin Trudeau, leader of the Liberals, would not freeze out a Jenrick-led British government. Clinton and John Major worked well on a range of issues, as did Tony Blair and George W Bush. Trump is mercurial, unpredictable and chaotic.

If Trump does return to the White House in November, that will, I think, be the defining moment in the life of the Labour government. Any hope of a return to “normal” politics will die alongside Kamala Harris’s presidential ambitions. Starmer’s government will have to find a new way of approaching the US-UK relationship: and what has, until now, been a “normal” exchange of volunteers between the two countries’ major centre-left parties may soon become a major diplomatic liability.

Now try this

During my holiday, I saw Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis. It’s a glorious mess. Coppola is both the director, the producer and the main financial backer of a film that is a very, very personal art project. He has left a huge amount of himself out on the canvas. The resulting movie has, at times, the structure, pacing and underlying logic of a Saturday morning dream. In some scenes, both money and time appear to be running out. (I don’t know if the scenes in which it appears that a character has stumbled over their lines are intentional or a result of the stretched budget, it could go either way.)

But I have to say, I loved it: it is mad, in places it is bad, but I go to the cinema in the hope of seeing an artist’s vision, and I certainly got that. Danny Leigh’s more equivocal review is here.

Top stories today

-

Upgraded | UK economic growth will accelerate this year and next as falling inflation and interest rates strengthen domestic demand, the IMF has said.

-

Aid curtailed | The Treasury is preparing to slash spending on overseas aid in the Budget after refusing to match Tory-era top-ups to compensate for development cash spent on asylum seekers in the country, said people familiar with the matter.

-

Grounded | Judges could impose house arrest as an alternative to jail as part a major review of sentencing aimed at easing the crisis in English and Welsh prisons. A fresh cohort of about 1,100 prisoners yesterday was released under emergency measures to free up cell space.

-

‘Whole water sector has failed’ | Water regulator Ofwat could be overhauled or even replaced under the most far-reaching review of the industry since it was privatised 35 years ago.

-

The council fighting against insolvency | William Wallis heads to Hampshire to discover how, even in this relatively prosperous part of southern England, the council is facing the largest funding gap of any council in the country in 2025-26, at £175mn.