Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

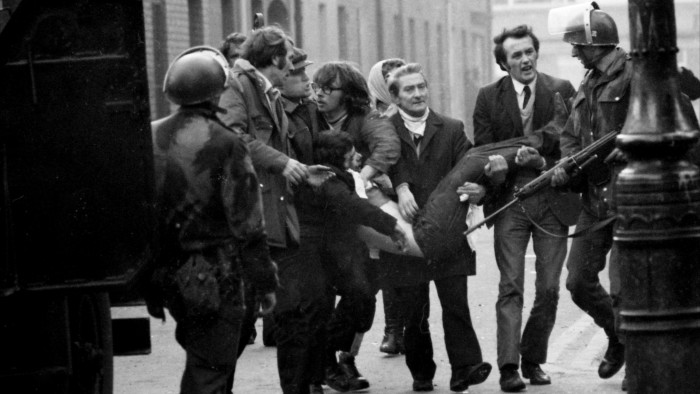

A former British paratrooper on Monday became the first person to stand trial for killings on Bloody Sunday in 1972, when soldiers opened fire on civil rights protesters in the Northern Irish city of Londonderry, fuelling three decades of conflict.

“Soldier F”, who cannot be named because of a court order, was shielded from view behind a black curtain in Belfast crown court as the high-profile case into one of the most brutal events in Northern Ireland’s Troubles got under way.

Dozens of relatives from Bloody Sunday families packed the public gallery for a trial which has put the issue of legacy crimes and the prosecution of British army veterans in the spotlight.

Soldier F has pleaded not guilty to the killings of James Wray, 22, and William McKinney, 26, on 30 January 1972. They were two of the 13 men killed after the Parachute Regiment opened fire in the city, also known as Derry, that day. He has also pleaded not guilty to five attempted murders. A 14th victim of Bloody Sunday died five months after the shooting.

John McKinney, a brother of William McKinney, called it a “momentous day”.

He said: “It has taken 53 years to get to this point, and we have battled all the odds to get here.”

Prosecutor Louis Mably KC told the court the Bloody Sunday shootings of unarmed civilians as they ran away were “unnecessary and gratuitous” and had been carried out “with intent to kill”.

Soldier F’s attempt to have the case quashed for lack of evidence failed last December. The trial comes as the UK and Ireland prepare to announce a new approach to investigations and prosecutions into atrocities during Northern Ireland’s Troubles, replacing the UK’s widely criticised Legacy Act.

That legislation, halting new inquests and civil proceedings into Troubles-era crimes, was passed unilaterally by the previous Conservative government but rejected by all political parties in Northern Ireland, as well as victims’ groups.

Belfast’s High Court struck down a key plank of the legislation, which would have offered immunity from prosecution to perpetrators who came forward, saying it broke international human rights law.

Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour government has vowed to repeal and replace the act in full and has been consulting closely with Ireland. Both sides have said an announcement of a new “framework” for investigations into legacy cases will happen soon.

If Soldier F is convicted in the non-jury trial, lawyers say the sentence he could serve is unclear.

An initial official UK inquiry into the atrocity was a whitewash, saying some shooting by the army had “bordered on the reckless” but that the protesters had fired on them first.

The victims were not exonerated until 2010, after a second inquiry, when then prime minister David Cameron told parliament the shootings were “unjustified and unjustifiable” and should “never, ever have happened”.

“I am deeply sorry,” he told MPs.

Soldier F was charged with the murders in 2019, but the public prosecution service of Northern Ireland at that time concluded that there was insufficient evidence to bring charges in the cases of 16 other former British soldiers.

Relatives of the victims marched to court holding a banner reading “Towards Justice”. Ciarán Shiels, a solicitor for many of the families, called on the court to show “moral courage”.

Unionists and military veterans have insisted that putting soldiers who served their country in Northern Ireland on trial would be a betrayal. The soldiers involved maintain they retaliated after coming under gunfire.

John Ross, a former paratrooper who knows Soldier F but served in a different battalion and was not involved in Bloody Sunday, told reporters the veteran was “in his 70s and not in the best of health” and had been “dragged to court to face trial”.

“It is not fair,” he said.

David Johnstone, Northern Ireland veterans commissioner, told reporters the legacy process was subjecting former soldiers to “wholesale demonisation”.

2 Comments

wwu30q

3vjytl