When Italian lawyer Mario Franzosi coined the term “Italian torpedo” in 1997 he had no idea it would go on to define generations of litigation — or that it would come back to haunt post-Brexit Britain.

The phrase refers to preemptively filing a lawsuit in a country such as Italy, whose courts are slow to resolve cases, in a bid to thwart an opponent’s legal action or force them to settle. The practice, which was employed for decades by litigators, has seen a resurgence in the UK after it left the EU and lost the legal protections limiting the “Italian torpedo”.

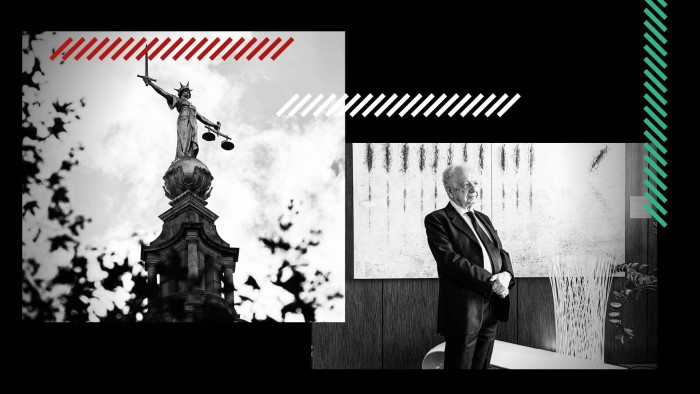

Speaking from his office in Milan, where he still works full time at the age of 91, Franzosi said the legal tactic has proven surprisingly resilient despite the EU clamping down on it over the past decade.

“You cannot choose the court of Milan because they know that they cannot be utilised to paralyse the system, but I can use another Italian slow-moving court and it works,” says Franzosi. “Less than before, but it still works.”

Franzosi, an intellectual property (IP) specialist, first wrote about the “Italian torpedo” in the European Intellectual Property Review journal nearly 30 years ago to describe a phenomenon he was observing in IP lawsuits.

But the legal weapon was soon deployed in other areas of litigation such as financial derivatives.

Richard Swallow, head of disputes at Slaughter and May, said that the “potential availability of the ‘Italian torpedo’— and whether to fire it or how to defend against it — was a vitally important early strategic question” in big cross-border litigation from the 1990s until EU rules changed in 2012.

“I’ve spent enough time in Italian court rooms to know,” Swallow said.

EU regulations were further tightened in 2015, clamping down on the practice across the bloc. But after the UK left in 2020, those rules no longer applied.

“That has brought the torpedo back into the litigator’s tactical armoury,” said Swallow.

Most current “torpedo” cases involve Italian municipalities challenging banks over derivatives agreements entered into before the 2008 financial crisis. While some of the banks are also Italian, they have sought faster resolution in English courts, but they are sometimes unable to get those rulings enforced as long as cases are lingering in Italian courts.

One of the first cases was brought by the municipality of Pesaro, a small Italian town on the Adriatic Coast, against former Italian bank Dexia, over interest rate swaps agreements entered into in 2003 and 2005.

Pesaro started court proceedings in Italy in June 2021, seeking to unwind or set aside the transactions. Dexia issued counter proceedings in England four months later, based on the assertion the transactions were governed by English law. Pesaro said it would contest the jurisdiction — though it never went ahead with such a challenge.

In 2022 Dexia won the English litigation. But proceedings in the court of Pesaro are still live and the bank is still trying to enforce the English judgment and have the Italian proceedings dismissed.

“With the UK there are a lot of financial transactions, so there are so many contracts agreed in the past that provide for a jurisdiction clause,” said Danilo Ferri, an Italian lawyer on secondment at Quinn Emanuel.

“At some point the panorama changed with Brexit but those agreements are still effective. The problem is born with that kind of transition,” he added.

Other cases include a derivatives dispute between Patrimonio del Trentino, which manages the assets of the Province of Trento, and Dexia, where there were parallel proceedings in London and Rome. The English court again ruled in Dexia’s favour last year.

Similar disputes have been heard post-Brexit between banks and the city of Milan and the province of Brescia, with the English courts mostly ruling in favour of the banks. Whether these rulings have been enforced in Italy, however, varies.

The appetite to file claims in a favourable country and obtain a judgment as quickly as possible may only increase. From July 2025, the UK will be a signatory to the 2019 Hague Convention, which provides for the mutual enforcement of judgments between UK and EU member courts. This could see parties try even harder to secure a judgment first.

“My expectation is that the Italian torpedo will live on after The Hague Convention,” said Andrew Lodder, a top English barrister who has acted on a number of the Italian municipality disputes.

“If the Italian proceedings are started first, then the recognition of the English judgment can be postponed until the Italian court has ruled,” Lodder said. “There will still be a real incentive to get in first in Italy and then seek to delay or oppose recognition in the Italian courts.”

Tom Clark, a litigation partner at Freshfields in London, said another reason for the “Italian torpedo” were the “perceived benefits of litigating in your home court”.

“That has long been a feature of complex international litigation and there’s no reason why that wouldn’t continue.”

FT series: Broken Justice

This is the first article in a series on Europe’s chronically underfunded justice system that risks undermining the rule of law and scaring off investors.

Part 1 How Europe let its courts decay

Part 2 ‘Millions of flies in the evidence room’ — inside Belgium’s Justice Palace

Part 3 The return of the ‘Italian torpedo’

Part 4 ‘Lawfare’ in Spain — the case against the Sanchez family

Other litigation tactics of days gone by have also re-emerged in Britain following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The so-called “anti-anti-suit injunction” — a turbocharged version of the “anti-suit injunction” that seeks to prohibit a person from pursuing proceedings in a foreign court — has been deployed recently to stop Russian courts claiming jurisdiction over disputes that should be heard in England.

The tactic was revived after Russia introduced new laws aimed at protecting Russian companies subject to western sanctions from lawsuits abroad.

This strategy is “a sign of how labyrinthine these satellite disputes can become,” said Swallow. In keeping with the whack-a-mole nature of litigation, when one tactic is stamped out another inevitably appears, he added.

For Franzosi, who said he may finally retire in 10 or 15 years, the legend of such tactics has come to define him.

“When I introduce myself [to people] they answer: ‘I think I remember Franzosi — the ‘torpedo master’.’”