Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The UK has given the go-ahead to German start-up Rocket Factory Augsburg to launch satellites from British soil, in what it hopes will be the first commercial mission to space from Europe.

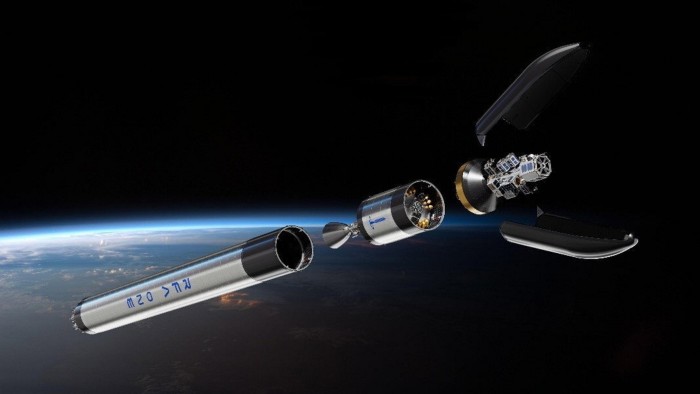

The Civil Aviation Authority on Thursday granted RFA permission to fly its 30-metre-tall RFA ONE microlauncher into orbit from SaxaVord spaceport in the Shetland Islands. While no date has been announced for the maiden flight, people familiar with the plans said it was aiming for the summer.

The licence for a vertical launch is the final authorisation needed to realise Britain’s decade-long ambition to become an independent spacefaring nation with its own privately developed, commercial spaceports.

It is also the first vertical launch licence to be granted to an orbital rocket in Europe, giving the UK an edge in the race with Norway’s Andøya spaceport to send satellites into space. Isar Aerospace, another German rocket start-up, is also hoping to launch from Andøya this year.

Aviation minister Mike Kane described the granting of the licence as “a landmark moment for RFA, SaxaVord and the UK space sector and moves the dial one step closer towards the first commercial vertical space launch in the UK”.

Colin Macleod, head of space regulation at the CAA, described the decision as a “huge step”. The UK now has blueprints for all the licensing required to launch satellites into orbit and would be “very competitive with other countries in terms of the time it takes to get approval”.

SaxaVord was one of six spaceport projects backed by the government in 2015 as part of a strategy to develop commercial launch capability that could tap into booming demand for services from space by 2018.

However, the others have either dropped out or struggled to win investment or customers, and the target for a first launch has been repeatedly pushed back. Cornwall spaceport has not recovered from the failed attempt at a horizontal launch in 2023 by Virgin Orbit, which has since collapsed.

Based on the isle of Unst, the northernmost inhabited island in the Shetland, the SaxaVord site will be used for missions to polar orbits where satellites will regularly pass over the same point of the earth as it rotates beneath them.

Jonas Kellner, head of marketing and communications at RFA, said this orbit was particularly suited to earth observation, communication and reconnaissance.

The UK has licensed RFA for 10 launches a year, a target that was not likely to be reached before the end of the decade, said Kellner.

RFA’s rocket is one of the largest microlaunchers under development and will be capable of carrying between 150kg and 1,300kg into space, depending on the destination.

However, the company still has to resolve problems that led to an explosion during the hotfire test of its nine engines last year. Kellner said work was under way to rebuild the rocket.

The company’s business case targets launch revenues of about €1.5bn, although RFA would not disclose how much of this was already booked.

Customers in the early stages would mainly be governments, military and public institutions, Kellner said, with commercial buyers waiting to assess the rocket’s success and reliability.

McKinsey in 2023 forecast that the industry faced an oversupply of rocket capacity from about 2028, when many new rockets are expected to come to market.

Kellner insisted that there would continue to be a market for smaller rockets such as RFA ONE to send satellites into orbit quickly and to precise orbits. This was the case particularly for military customers.

“The key word here is responsive launch, the launch of satellites at short notice for communications and reconnaissance. We all know the situation in Ukraine.”