Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Artificial intelligence myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Two years ago, a New York company enforced an “attorney exclusion list” at its venues, including Madison Square Garden and Radio City Music Hall, sparking a civil rights clash. Using artificial intelligence-enabled facial recognition technology, MSG Entertainment identified lawyers from firms involved in litigation against the company and barred them from entering concerts, shows and ice hockey and basketball games. Naturally, being lawyers, they sued, denouncing the ban as dystopian.

Not everyone sympathises with lawyers even when they are prevented from watching the Rockettes’ Christmas spectacular. When the tech entrepreneur and investor Reid Hoffman discussed this ban in a recent lecture in London, one veteran chief executive sitting next to me muttered: “Good.” But the incident neatly illustrates how our uses of technology can lead to messy wrangles over commercial interests, personal gripes, legal precedents and civil rights.

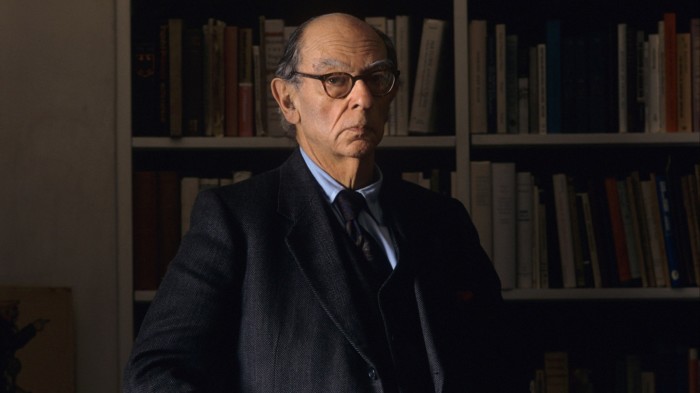

As Hoffman explained, such disputes are just the latest tech-enabled twists in age-old tussles over competing values. In democratic societies, at least, there are usually ways of reaching negotiated trade-offs in controversies over security and privacy, private profit and public good, individual freedom and the collective interest, often in the courts. Such clashes tend to revolve around what the British philosopher Isaiah Berlin called negative and positive concepts of liberty. Berlin defined negative liberty as freedom from external barriers or constraints. Positive liberty he viewed as the possibility of exercising individual agency and taking control of one’s life.

As Berlin argued, and Hoffman amplified in his lecture honouring him, these claims to liberty are often incompatible and sometimes incommensurable, meaning they exist in different moral planes that cannot be measured against each other. The best that can be expected is an imperfect compromise that is more or less acceptable to all parties. Democracy is a mucky, but pragmatic, business.

One concern about the accelerating use of AI, however, is that the technology might strip humans of agency and the ability to arbitrate in such disputes by enforcing rigid algorithmic rules. In his latest book, Nexus, the Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari relabels AI as alien intelligence, because the technology is emerging as a new form of intelligence with its own agency. “AI is an unprecedented threat to humanity because it is the first technology in history that can make decisions and create new ideas by itself,” Harari writes. Nuclear bombs cannot choose where they are dropped. Autonomous drones, on the other hand, could decide by themselves whom to kill.

However, Hoffman implicitly rejected Harari’s alarmist take on AI. Our tendency to fixate on how technology endangered the static present obscured the creative possibilities of a fluid future, he suggested. Rather than eroding human agency, AI could be designed to enhance it. Its purpose should be to empower humans, giving them “superagency”, as Hoffman called it. The smart use of AI could offer individuals “new superpowers”, which they could apply to their lives in unrestricted, inventive and personally relevant ways.

By using generative AI tools, such as ChatGPT, individuals could quickly acquire the most useful skills, help teach their children maths and evaluate complex terms and conditions in legal contracts. They would become smarter employees and better citizens, benefiting from a decentralised and distributed form of positive liberty and enabled to pursue their own paths. “I think of tools like ChatGPT as a new form of informational GPS,” he said.

Hoffman’s optimism is a welcome corrective to some of the doomsterish debate about AI. But some may also consider it delusional. Consider another version of our technological future currently being built: China. A recent report from the Washington-based Information Technology and Innovation Foundation said it was only a matter of time before China caught up with — if not surpassed — the US in AI. In some areas, such as facial recognition technology, China may already be ahead.

The clear intent of the country’s tech strategy is to empower the Chinese Communist party more than its citizens. Some researchers have talked about how China’s highly intrusive AI-enabled surveillance state is imprisoning people in an “invisible cage”. Depending on how we use it, AI is the frenemy of freedom. As Berlin warned, and Hoffman acknowledged, authoritarian regimes can hijack the rhetoric of positive liberty to impose their own dogmatic interpretation of the collective good.