Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The computational “law” that made Nvidia the world’s most valuable company is starting to break down. This is not the famous Moore’s Law, the semiconductor-industry maxim that chip performance will increase by doubling transistor density every two years.

For many in Silicon Valley, Moore’s Law has been displaced as the dominant predictor of technological progress by a new concept: the “scaling law” of artificial intelligence. This posits that putting more data into a bigger AI model — in turn, requiring more computing power — delivers smarter systems. This insight put a rocket under AI’s progress, transforming the focus of development from solving tough science problems to the more straightforward engineering challenge of building ever-bigger clusters of chips — usually Nvidia’s.

The scaling law had its coming-out moment with the launch of ChatGPT. The breakneck pace of improvement in AI systems in the two years since then seemed to suggest the rule might hold true right until we reach some kind of “super intelligence”, perhaps within this decade. Over the past month, however, industry rumblings have grown louder that the latest models from the likes of OpenAI, Google and Anthropic have not shown the expected improvements in line with the scaling law’s projections.

“The 2010s were the age of scaling, now we’re back in the age of wonder and discovery once again,” OpenAI co-founder Ilya Sutskever told Reuters recently. This is the man who a year ago said he thought it was “pretty likely the entire surface of the earth will be covered with solar panels and data centres” to power AI.

Until recently, the scaling law was applied to “pre-training”: the foundational step in building a large AI model. Now, AI executives, researchers and investors are conceding that AI model capabilities are — as Marc Andreessen put it on his podcast — “topping out” on pre-training alone, meaning that more work is required after the model is built to keep the advances coming.

Some of the scaling law’s earliest adherents such as Microsoft chief Satya Nadella, have attempted to recast its definition. It doesn’t matter if pre-training yields shrinking returns, defenders argue, because models can now “reason” when asked a complex question. “We are seeing the emergence of a new scaling law,” Nadella said recently, referring to OpenAI’s new o1 model. But this kind of fudging should make Nvidia’s investors nervous.

Of course, the scaling “law” was never an ironclad rule, just as there was no inherent factor that allowed engineers at Intel to keep increasing transistor density in line with Moore’s Law. Rather, these concepts serve as organising principles for the industry, driving competition.

Nonetheless, the scaling law hypothesis has fuelled “fear of missing out” on the next big tech transition, leading to unprecedented investment by Big Tech on AI. Capital expenditures at Microsoft, Meta, Amazon and Google are set to exceed $200bn this year and top $300bn next year, according to Morgan Stanley Nobody wants to be last to build super intelligence.

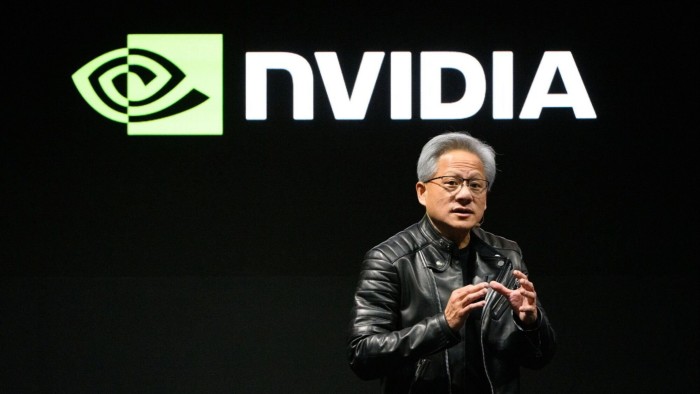

But if bigger no longer means better in AI, will those plans be curtailed? Nvidia stands to suffer more than most if they are. When the chipmaker reported its earnings last week, the first question from analysts was about scaling laws. Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s chief executive, insisted pre-training scaling was “intact” but admitted it is “not enough” by itself. The good news for Nvidia, Huang argued, is that the solution will require even more of its chips: so-called “test time scaling”, as AI systems like OpenAI’s o1 have to “think” for longer to come up with smarter responses.

This may well be true. While training has soaked up most of Nvidia’s chips so far, demand for computing power for “inference” — or how models respond to each individual query — is expected to grow rapidly as more AI applications emerge.

People involved in the construction of this AI infrastructure believe that the industry is going to be playing catch-up on inference for at least another year. “Right now, this is a market that’s going to need more chips, not less,” Microsoft president Brad Smith told me.

But longer term, the chase for chips to power ever-larger models before they are rolled out has been replaced by something that is more closely tied to AI usage. Most businesses are still searching for AI’s killer app, especially in areas that would require the nascent “reasoning” capabilities of o1. Nvidia became the world’s most valuable company during the speculative phase of the AI buildout. The scaling law debate underlines just how much its future depends on Big Tech getting tangible returns on those huge investments.

tim.bradshaw@ft.com